At the Malverns Classic Festival there were a bunch of riders with Bowhead adaptive trikes taking part in the racing, which was great to see. But then this rolled by and I realised it was something really different. And then I got chatting to the guy riding it – Noel Joyce – and discovered it’s some really really different. Quite possibly the most interesting bike I’ve seen this year. Thanks very much to Noel – who is both its rider and its creator – for taking the time to tell me more about it.

The bike is an open-source project that we’ve been developing at New York University, it’s called Project Mjolnir. If anyone doesn’t know what Mjolnir was, it was Thor’s hammer – so we look at this as an instrument to break down barriers for people with disabilities much like Thor used his hammer to break down or smite his enemies and all that sort of stuff. But also another little bit of background to the name was in Halo video games the Master Chief’s armour was Mjolnir class armour and I was a fan of those games! So that’s that’s a little bit about the name of the project.

What it is, is an open-source adaptive mountain bike for wheelchair users. Anyone with a disability who wants to build their own bike can get those files online and use them to have parts made to assemble their own frame, and then just put regular bike parts onto that frame and have an adaptive mountain bike. If they don’t have the means to build it, or anywhere they can go to get those parts made, they can reach out to me or any of the guys that are working on the project to find contacts that can make those parts. So that’s what we’re trying to do: we’re trying to decrease the barrier to entry for adaptive riders. Because the truth of the matter is that is the most prohibitive part of it. A lot of trails are actually pretty accessible but the technology is not, so by trying to create the scenario where people can build their own bikes we can decrease the cost by two thirds.

If we look at say the price of getting say a Lasher for example into the UK you’re probably closing in on more than £20,000 by time you pay import tax and all the rest of it. We can build one of these for about 8,000EUR.

So is it all CNC’d aluminium?

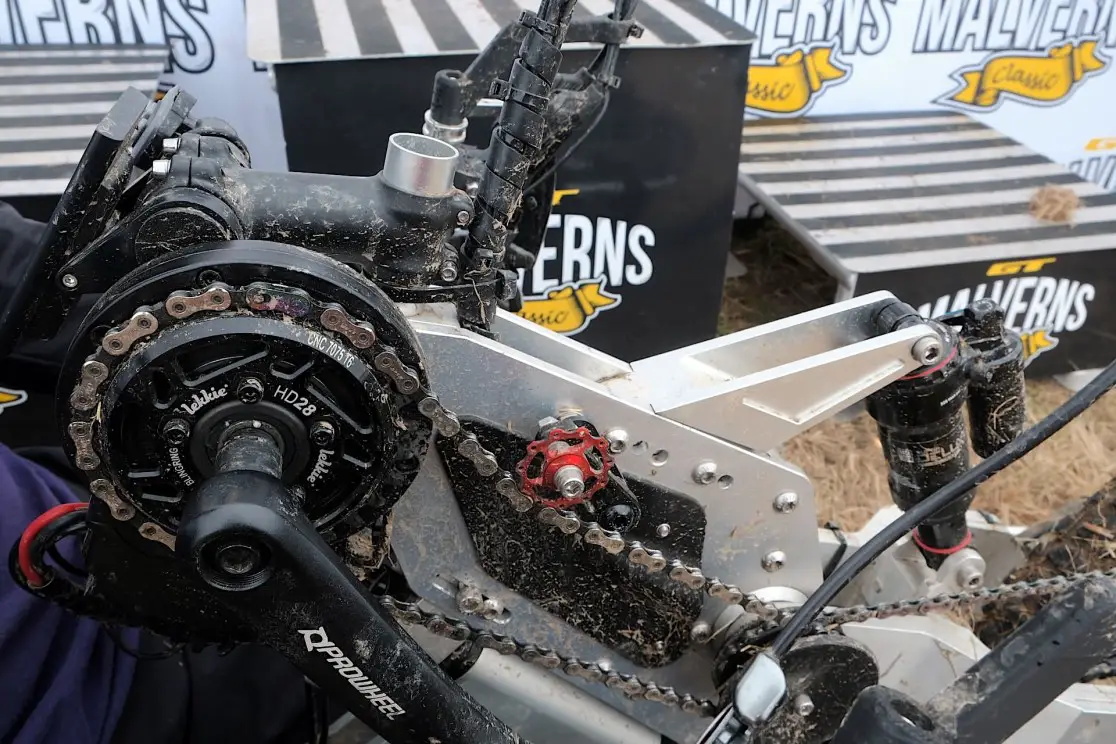

This current one that you’re looking at right now is all 7075 T6 CNC’d aluminium. Everything is machined. It’s all bolted together by standard metric bolts. But the thing is that you can change things on this bike. If you think ‘right I want the head tube to have a steeper angle’, you can change two plates to do that. If you want longer travel in the rear, or shorter travel in the rear, you can do that by changing two plates. We’re thinking it’s almost more like a platform than just a bike. We know that we can start with a rigid version of this ,and build an entire bike for less than 3,000EUR. And then people can actually go from that to a full suspension bike on the same frame by just changing modular components. So it could be very cheap, but like any really good bike you get full works parts and end up with a pretty expensive machine too!

How many parts does it take to make the frame?

Oh wow now you’re asking the question that I honestly don’t have the exact answer to! But it’s definitely a couple of hundred different parts to make the frame. There’s a lot of smaller bits and pieces that you’re probably not seeing like parts that make up a pedal, that kind of thing.

I’ve made it open source for the reason that people can actually get a hold of those files and amend those and change those parts and if they found a way to simplify something they can do that. And then the community can benefit from that. Not that it’s huge right now but we have a few people who mess around with it.

So this one is an electric assisted hand cycle and so are there different versions of it for different capabilities or are they all hand cycles?

Yes the short answer is yes we can start amending things like hand controls and stuff like that for different types of disability.

So if you had like a single-sided weakness or something there’s a like a different adaptation for that?

Well the system drive can help a lot with that but I think throttle assistance definitely helps. This actually has the throttle on it as well. But where we see a big advantage with having a modular platform like this is that we’re able to look at someone with a disability and go ‘okay what will work for you?’, and we can start to amend this platform straight away. So for example in Shanghai in China we had a lady who had spinal bifida and much smaller legs and we mounted the foot hoops to the mainframe since she was much smaller, so we were able to set up for her. We were able to, in Idaho, design brake levers to suit individuals with limited dexterity as well. For example on here I’ve 3D printed these parts to make a dual brake lever, rather than a specialist setup with a Hope lever or whatever it might be, that can be quite expensive.

There are details like this all over the bike – little bits of design that keep costs down and make it easier to build the bike up from readily available parts. Noel says he likes to exploit SRAM’s engineering led approach, where they introduce standardisation as part of bringing efficiency into the manufacturing process. The standard flip-flop brake levers can be fitted neatly onto the 3D printed adaptor that Noel designed, creating a double brake lever for the two rear wheels.

On the other pedal, Noel has an AXS wireless shifter for the gears – which he notes could be moved to be chin operated. He tells me that SRAM has just patented voice activated controls, which will further open up options. Showing there’s no end to his innovativeness, he’s also taken a standard suspension lockout lever system, and turned it into a hand brake – allowing riders to transfer into the bike without it rolling away from them.

So anything that we want to do we can do with this. It’s not limited to an individual being told ‘That’s your bike and that’s how it’s going to work’. An individual with a specific need can look at it and go ‘I need help with that specific thing, can you help me with it?’

What’s the technology to stop it tipping?

I’ve put about 200mm of travel on all three wheels so when I lean it, it doesn’t want to go over, there’s a lot of active movement there, and a lot of camber in the rear wheels which keeps it very planted. Then as well as that, because we’re using the bigger wheels it rolls over obstacles much more effectively. When you get those smaller wheels they tend to get caught in ruts and stuff like that. It’s 27.5 but you can put 29s on this easily. We have room here and also at the rear – it doesn’t matter because it’s just bolted in at the axle. The benefits of that again is, if someone broke a wheel, it’s just a standard boost wheel that can be put into the front, and same with the rear. Everything is a standard bicycle component on this bike.

We’re building an open source project – but why? Because people with disabilities have much more limited time to be involved in the sport, because the body just deteriorates that much faster – if we’re getting honest about it all. For me, when I kept breaking parts for my bike I was being told these really long lead times to get a new part. So that’s like if you tell me six weeks, you’re telling me six months – it’s the same difference. I lose so much time not being able to ride my bike, and then the parts are so expensive as well. So it becomes where you’re at the mercy of a manufacturer, and on top of that you have to wait a long time. For me it was ‘like let’s do something where we can make a bike that can be repaired in the same time it takes to repair a regular bike’. So any of the machined parts on here, if you’re willing to pay the money, you can get one made in three days – and you can get one in two weeks if you want to do it a bit more cheaply. That’s an acceptable amount of time, right? And we make it more cost effective as well. For example I designed a part for a secondary brake on this. It was a 20EUR part to make and I got it in two weeks. It’s about making sure that people with disabilities don’t have to face exorbitant prices, that they don’t have to face long lead times, and that they can change and develop the bike to suit themselves as well.

It’s like the Linux of the bike world!

Someone said to me it’s a B-ikea, it’s like an IKEA thing that you can hack, right? So B-ikea!

I like the community idea though of Linux?

It’s easier to contribute to an open source software I suppose. Open source hardware can be a bit more difficult. The adaptive mountain biking community is quite small, but it’s a community of very dedicated people interested in the sport. What it takes to even get to an event like this requires a ridiculous amount of effort. I’ve got to get up here to do this, I have to pack a car full of wheelchairs and bikes and all this crap, and turn up at a place. If it rains it’s going to be horrible – it’s bad for able-bodied people but a magnitude worse for people with disabilities. I think that because it’s such a tightly knit community with such an interest in the sport, when we get a few of them built and people are riding them and amending them and changing them, then we’re going to see a lot of cool stuff happening.

It’ll be like an exponential kind of technological improvement! You alluded there to how difficult it is to get out and ride and you said before that your mate is here with you that you wouldn’t be able to ride without him, so can you tell us a little bit about that?

I didn’t get back on an adaptive bike up until only just four years ago. It happened to be that I live right next door to Robert and I’d been out messing around on a really old like terrible excuse for a bike, and uh he said you should come to the Sleive Blooms which is the mountains and hills near where we live. And I said ‘well I don’t know if I’m going to be able to manage, but I could go on the fire roads – let’s check out the fire roads’. So we went and we got to the top of the first blue trail and he said ‘why don’t you try?’ and we went down, and it’s like the bug bit again. It would have been 15 years since the accident and I was like ‘okay, this is why I was doing it in the first place. This feeling’. It’s only for him saying to come out – it wouldn’t have happened without him and I wouldn’t be talking to you today, for sure. I wouldn’t have had the nerve to go and do it.

Every time we go out, I go with him, and he’s like my eyes on a new trail. Because he’s much higher than me, he’ll say ‘go fast here, slow down here, coming into a berm here’. I trust everything he’s telling me as we go down the trail, and there’s been very a minimal amount of crashes as a result. You need to have a riding partner – you need to have them when you’re out there in the further reaches I suppose.

Because it’s not like you can push your bike home – if something breaks, it’s consequential.

Yes. So the story behind this was when I started thinking about adaptive mountain bikes I reached out to a number of manufacturers and I said ‘Look I have these ideas about what I want for my bike and I’m happy to give them to you if you will build a bike for me. I have no problem giving you that intellectual property’. My background is industrial design and I teach design and innovation at New York University. Luckily for me they just thought I was some crackpot and had no interest in listening to me, so I had to go and do it myself!

I found a company that were willing to execute on some of those ideas and I got that bike built and I went out and subsequently kept breaking that. One day I was out and I hit like a little triple, landed really hard on the rear and broke a carbon a-arm on it, and they told me it was going to be ridiculous money and a long time to get that part replaced. I went home that night and I got onto the computer, into CAD, and I redesigned the same part in a couple of hours. I had four of those units made – for half the price they were quoting me – from aluminium and I had them in two weeks.

So it was like ‘Okay if I can do that, I can build an entire bike like that. And if we can do that, then we can make sure that no one is in that situation again’. It was that day on the trail that I got the fear again from the crash – because you’re there going ‘Right this is what it feels like to be stuck and not able to get out’. Which was what it was like the first time when I broke my back. Just there in your mind – you never want to have that again, so making sure that bike never leaves you in that situation. You have the power to do something about that by designing the bike to to be robust.

Because it’s modular, does that make it easier to transport as well? Could you fold it up and put it into something smaller than some of the other trikes?

I take the front wheel off and I put a little wheelbarrow wheel on it and it just fits in the back of my car then. So it’s a little bit like shorter from that perspective – but not folding. People have said that could you make a foldable version but you’re going to compromise frame strength and stuff like that. I think that people comment on weight as well, but I think weight on these things is sort of irrelevant because they have assistive drive. You don’t really need to worry so much about that. The thing I would consider is how do you lug them around, and then that’s about us thinking about how do we make it easy for people to move around and not sacrifice the strength of the bike

But I guess because it’s modular and people can adapt it to their needs, somebody could design the sort of commuter-light version of it?

This year we built one in Reno, up in the Sierra Nevadas. We did a camp there, we built a bike there. We built one in Idaho as well, and in Idaho we had over 65 adaptive riders at that event. We had a group of people with disabilities working on that build, and there was loads of comments about ‘could we do this, could we do that?’ and I was like ‘Yes, you can. Because you’re building the bike right now, and you’re having those ideas, you can do those things’. What came out of it as well is ‘Can we build a kids’ version?’, ‘Can we do a gravel version?’. Yes, we can do all of those things, and that’s what I think is important about this project is allowing people the flexibility to do that. When people say to me ‘Have you thought about this?’, I go ‘No, but you have. Now you can do something about it.’

It’s a really interesting innovation prospect, having it as open source, but I think also it’s a different model of construction and manufacturing delivery as well. You’re not shipping parts all over the world – you can get them made locally.

One of the elements of the brief that we put together for ourselves on this was that you can build one anywhere. So today if you said to me I want to build one of these bikes, we can order the parts, have them landed in two weeks, in the meantime buy our motor and all our bike parts and by week four we will have a bike built. We can build one of these in two days. So the lead time is not six months for anyone who wants an adaptive bike, it’s four weeks. Because they can build them anywhere and use standard fasteners. That’s what we’ve done in Reno and in Idaho – we spent two days building the bike and then we brought it out and rode it on the third day. When you see that happening, it appears to be impossible at the beginning – but then we do it and it just looks like magic.

Well I think it’s an amazing thing. I’m really impressed. Thanks for doing it and thanks for talking to us.

If you’re as buzzing as I am about the possibilities this bike offers, you can find out more at the Project Mjolnir website, or follow Noel on Instagram. If you come up with an exciting addition to or variation on the design, please keep us posted!