Home › Forums › Bike Forum › Greater than 90 degree head angle.

- This topic has 23 replies, 17 voices, and was last updated 8 years ago by greyspoke.

-

Greater than 90 degree head angle.

-

opusoneFree MemberPosted 8 years ago

Bear with me…

I was chatting with one of my mates about what effect a greater than 90 degree head angle, i.e. backwards pointing forks, would have on the stability/use of a bike and whether it would make it completely unrideable or merely extremely difficult and highly unintuitive to ride. Does anyone know of a video or similar where someone’s tried to do this for funsies?

honourablegeorgeFull MemberPosted 8 years agoNot sure it would be any fun…. think difficult/uncomfortable rather than impossible.

Would need to lenthen the TT to avoid any toe overlap problems, which might alleciate things a bit Of course, if you didn’t, then it might get to be impossible.

jemimaFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThink shopping trolley handling… which with only two wheels would make the bike want to fall over all the time I think.

Rubber_BuccaneerFull MemberPosted 8 years agoI think it would be a bit nervy at speed but mostly, like said above, you’d have trouble choosing a length of top tube where you could reach the bars but the wheel wasn’t hitting your feet when you steer

philjuniorFree MemberPosted 8 years agoYou’d end up with negative trail unless you made the forks bend backwards. I’m not sure if (ignoring toe overlap/TT length issues – nothing wrong with linkage steering) you could get something inherently rideable or not though. It might avoid “flop” at low speeds…

rusty90Free MemberPosted 8 years agoMotor pacing (‘stayer’) bikes used to have a 24″ wheel and reversed front forks to get the rider closer to the back of the motor bike. They could go round a track at 50 mph, so not completely unstable.

twistyFree MemberPosted 8 years ago

twistyFree MemberPosted 8 years agoIf the rake is also reversed then it works because gravity will still be centering the wheel.

medoramasFree MemberPosted 8 years agoYou’d probably end up with “halfords-style” stem to keep your CoG central!

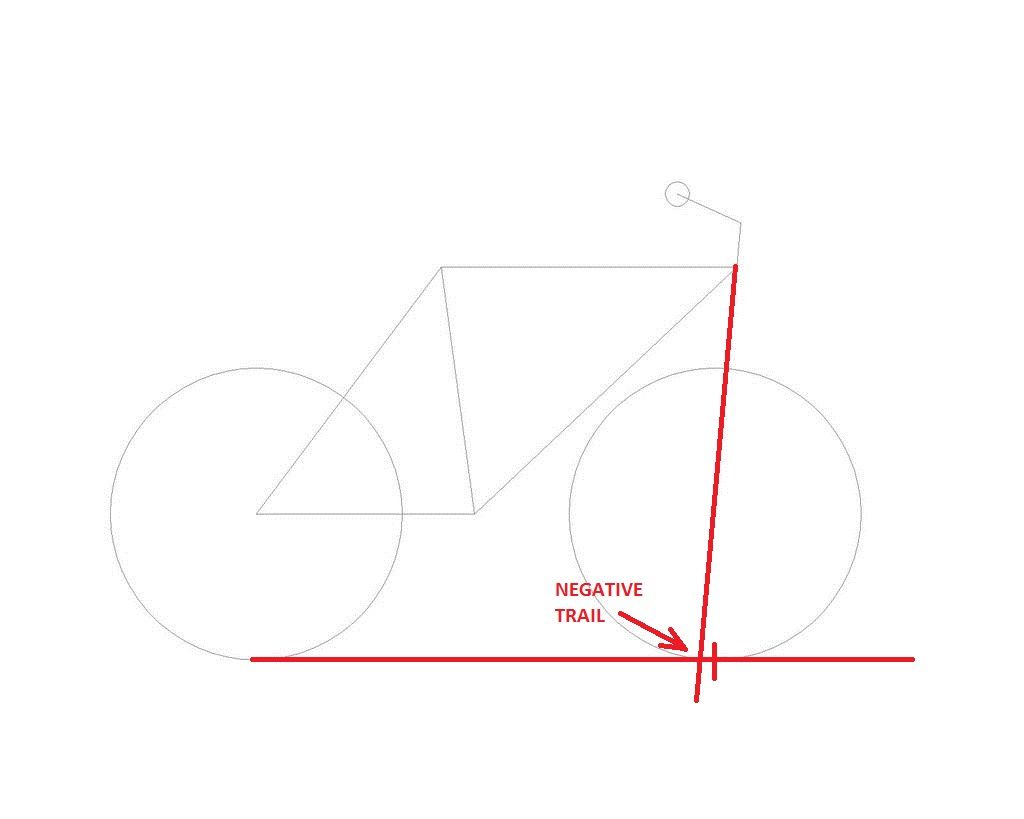

As per my super-techy CAD work (95° HA):

😀

tillydogFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThose motor pacing bikes will be made more stable by the “reversed” forks, as they increase the amount of trail. Neither of them have head angles >90 degrees, though.

Trail makes the bike “self balancing” once it’s moving – tip the bike to one side, and the weight of the bike/rider acting on the offset between the steering axis and the contact point makes the steering turn in the direction needed to stop the bike falling over. More trail = more stability (up to a point) and more effort needed by the rider to turn (up to a point).

The CAD bike does have a >90 degree head angle, but also has negative trail:

The negative trail in itself will make the bike dynamically unstable – once moving, as soon as the bike moves off vertical, the steering will want to turn away from the lean, not into it. Maybe not un-rideable, but must be pretty damn close, I would guess.

If the forks of the CAD bike were kicked forwards, though, it could go back into positive trail but still with the negative head angle, which might make it “interesting”. As I understand it, the head angle will affect the very low speed stability due to the jacking effect on the front of the bike as the steering is turned – positive head angles (<90°) will tend to make the steering self centre, but negative head angles (>90°) will tend to make it flop to one side or another. Once moving, though, the trail will tend to work against this, so maybe the bike would be unstable at very slow speeds, but become stable if the rider could control this until some speed was built up (watch out when you slow down again!) or maybe it would just be like a bike with very low trail, I don’t know.

opusoneFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThe negative trail in itself will make the bike dynamically unstable – once moving, as soon as the bike moves off vertical, the steering will want to turn away from the lean, not into it. Maybe not un-rideable, but must be pretty damn close, I would guess.

It’s this effect that I was driving at. The positive trail (I understand the concept but didn’t know the name for it until just now) of a bike is something we all use intuitively and I don’t think I really had an appreciation of until quite recently. Some things, e.g. riding fakie, involve “unlearning” it, or at least using it in a different way.

Now that I’ve learnt the term, i just had a quick look at wikipedia and it says these bikes are rideable but feel very unstable.

PS – The reason we got talking about it was because of a video where someone built a bike where turning the bars one way turns the wheel the opposite direction. Surprise surprise, it’s very difficult to ride and (in the video) comedy ensues. I thought doing a similar video, but with a bike that looks (to the untrained eye) like a relatively normal bike, but is very difficult to ride because of a facet of bike design/bike mechanics that probably isn’t widely known or appreciated would be quite interesting.

rsFree MemberPosted 8 years agoi’m sure there’s been a few ebay add’s posted on here with forks on backwards, seemed that nobody died 😯

bencooperFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThe negative trail in itself will make the bike dynamically unstable – once moving, as soon as the bike moves off vertical, the steering will want to turn away from the lean, not into it.

Only talking about my experience with actually riding bikes with steering like this, but this isn’t what happens. There are two balancing effects:

Lean the bike over, and it tends to turn more into the turn because of “jacking” – the bike is trying to get lower,so the steering flops over. Do this when the bike is stationary and it’s obvious.

But when riding, this has the effect of trying to make the turn harder than the lean is adequate for, so it tries to straighten up. Get the trail right, and these two balance.

That Streetglider up there is one of the most stable recumbents I’ve ever ridden – on a smoothish car park it’s possible to ride no-hands in lazy figure-8s, and in general riding it’s beautifully well behaved*.

These two competing effects – the jacking and the the subsequent balancing when riding – are the exact same effects you see with a conventional steering, by the way. I’m reasonably convinced that a 90deg head tube with reversed forks is just as stable and rideable as the conventional setup, it’s a biomechanical reason that normal bikes don’t use it.

*Early versions developed an entertaining tank slapper at around 30mph, but that was down to flexy steering linkages.

opusoneFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThat Streetglider up there is one of the most stable recumbents I’ve ever ridden

Eyeballing them, they both have strongly positive trail (if that’s the correct term). The backwards pointing forks means that the tyre touches the ground well behind the steering axis.

amediasFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThe reason we got talking about it was because of a video where someone built a bike where turning the bars one way turns the wheel the opposite direction

We have one of these down at the workshop (from a circus), it is very very difficult to ride!

the main problem isn’t the fact that the bars turn the wrong way, with a little bit of practise and determination you can ‘force’ yourself to deal with that, the difficulty is that it’s very difficult to deal with the fact that when you turn the bars the ‘wrong way’ it makes it lean opposite to what you expect, and that just throws off X years of learned reflexes and you struggle to correct it.

I’ve managed to ride across the yard a few time on it, the thing that actually helped me was learning to ride it with my eyes shut, it helped loads as I was then feeling it and didn’t have the confusing input from my eyes to mess it up, worked a treat 🙂

One of the lads can ride it OK after about 8hrs practise, but only in circles!

medoramasFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThere is an interesting video on YT (search for a channel “Smarter Everyday”), where a guy learns to ride one of these “wrong” bikes. He tries everyday, then finally is able to ride it – but looses the ability to ride the normal bike!

tillydogFree MemberPosted 8 years agoOnly talking about my experience with actually riding bikes with steering like this…

Do you mean the recumbents in your pictures? They have conventional, positive trail, and quite a lot of it, so would be expected to be stable (but read on). I’m not a bike builder or designer (I doff my hat to those of you that are), but recall some stuff from my Engineering degree.

That Streetglider up there is one of the most stable recumbents I’ve ever ridden – on a smoothish car park it’s possible to ride no-hands in lazy figure-8s, and in general riding it’s beautifully well behaved*.

…

I’m reasonably convinced that a 90deg head tube with reversed forks is just as stable and rideable as the conventional setup, it’s a biomechanical reason that normal bikes don’t use it.

*Early versions developed an entertaining tank slapper at around 30mph, but that was down to flexy steering linkages.

This whole topic was introduced to us in uni. as the “tail wheel shimmy” problem that was studied and analysed in the early days of aircraft design – Depending on the combination of trail, castor angle (= head tube angle in this case), wheel size, etc. there can be a natural resonant frequency which gets triggered at a certain speed. Once triggered (e.g. by wheel imperfections, road bumps, etc.) this results in a self sustaining oscillation (=tank slapper in this case). How sensitive the system is, how quickly the oscillation builds up, and how “bad” it gets are also determined by the geometry. Stiff steering linkages, or steering dampers seem to be acceptable ways to minimise the problem, but it is still inherently present unless something is changed that moves the geometry to a less sensitive or even a stable area (maybe at the expense of compromising other aspects), or shifts the resonant frequency to somewhere it is less likely to be triggered.

This pdf is a thorough analysis of it, but the interesting bits are almost hidden by the maths. (Might be interesting to read the summary on p32).

What happens in the real world is what matters, but hopefully the theory gives some insight into why it happens.

(This is different to the ‘backwards bike’ problem – that’s “just” a matter of learning, and the youtube video is fascinating 🙂 )

opusoneFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThere is an interesting video on YT (search for a channel “Smarter Everyday”), where a guy learns to ride one of these “wrong” bikes. He tries everyday, then finally is able to ride it – but looses the ability to ride the normal bike!

I was referring to that video above when I said it was that which set me off thinking about this.

If I were being really mean, I would say that the larger point(s) that he was trying to make – that we rely on muscle memory for lots of things and that there is a large gulf between knowledge and understanding, or between knowing what you have to do and being able to do it – didn’t strike me, as someone who has, for instance, learned to play the piano, as a particularly profound insight.

bencooperFree MemberPosted 8 years agoDepending on the combination of trail, castor angle (= head tube angle in this case), wheel size, etc. there can be a natural resonant frequency which gets triggered at a certain speed.

Yes – though I think in the Streetglider case it wasn’t a natural resonant frequency of the “tail wheel”, it was a resonant frequency of the steering rod and especially the stem linkage connecting the fork to the steering rod. I had an older version of the bike which had the problem, I replaced that part with a much stiffer one and that cured the problem. It wasn’t actually having damping in the pivots or anything, they were still running free.

RetrodirectFree MemberPosted 8 years agoI’m reasonably convinced that a 90deg head tube with reversed forks is just as stable and rideable as the conventional setup, it’s a biomechanical reason that normal bikes don’t use it.

Stable yes, rideable is debatable.

According to the calpoly uni 2wheeled vehicle chassis design course atleast … the steeper the headangle (for a given trail and COG) the less force will be exerted through the handlebar to allow you to feel for what the bike is doing. Holding the bike in a steady state turn, straightening the bike and turning harder all exert different forces at the handlebar. These forces are important for the rider’s ability to control the bike.

a 90degree headangle will result in a bike with no “feel”.

I can only assume this means a negative headangle will result in the forces which allow you to feel the state of the bike will be reversed.

I messed about making a bike with a 75degree headangle and 15mm rake fork, it was a fairly wicked thing to ride at times. Turned on a dime, which is what I wanted it for, but the steering didn’t give very much feedback and it was a difficult to ride. Other bikes with similar trail and more wheelflop handled a lot more intuitively.

The issue with a lot of the analyses above are that none of them are attempting to put the human into the equation. Hands-free stability theories will agree with what you are saying, Ben. But when you have a human rider as the control of a closed loop system the best bike examples have feedback that comes from wheelflop from a non-vertical headtube.

dangeourbrainFree MemberPosted 8 years agoThe reason we got talking about it was because of a video where someone built a bike where turning the bars one way turns the wheel the opposite direction

They had one of these every year at an annual find raising gala back when I was a kid, ride it 20m round a cone at the end and back and win a tenner or some such. Every year I tried several times and failed long before the cone. Rumour had it someone once managed it but I never saw anyone manage more than about 10′.

Oddly the memory thereof popped into my head just the other day for no apparent reason.

greyspokeFree MemberPosted 8 years agoAn important factor in low-speed stability is how the centre of gravity falls/rises as the bike flops over and the steering turns. The bike will stabilise at a steering angle where the cg is lowest (you can see this by looking at how a the steering of a static bike changes as you lean it over). This “cg lowering as the steering turns to correct the lean” effect depends on having some trail, unless you make an extreme design where the cg does funny things like these guys did[/url]. (They are far too dismissive of #David Jones[/url] work there I think.)

The problem with a head angle at >90 degrees may be that the cg lowering effect is not limited. My dodgy mental geometry imagination indicates that for any angle of lean, the cg would be lowest if the wheel turned a full 90 degree, but it would take some proper geometry to confirm that. With a <90 head angle, there is an minimum cg height point dependent on a combination of trail and head angle.

The topic ‘Greater than 90 degree head angle.’ is closed to new replies.