How Belgian professional Ben Berden lost it all – and then found it again, on the other side of the Atlantic.

Words by Greg Keller. Photos as credited.

First published in Grit.cx Issue 1: October 2014

The drive from one side of Belgium to the other had him cramped and tired. Two and a half hours by car to West Flanders, a two-hour practice; then three hours back to his home in the east.

He had won a few races in his local series and made the selection to participate in a junior exhibition race before one of the Super Prestige races, the Daytona 500 of cyclocross events in Belgium. Tens of thousands of spectators. Millions more watching on TV. The main event for any child, let alone any cyclocross racer. His performance earned him the ticket to a very select training camp for promising kids. Bike racing was becoming part of him. To race cyclocross professionally was starting to look like an option. That, or labor on the horse farm his dad owned as he was too small to combat the other Belgian boys in the kermesses. Road racing was not going to be a path.

He stretched his legs after the long drive, and his dad helped extract his bike out of the back of the car. The pair meandered over to where the other juniors were standing and said very little. He just stood there and watched. An older rider was attracting the attention of the other juniors. He rode by them slowly, literally tied into his cross bike with toe clips and straps. He paused, track standing, then carefully laid himself and his bike down on its side, still connected. More or less crashing in slow motion; intentionally. Still strapped in, with his hands never leaving the bars, he magically rose using body leverage and all the skills he learned riding bikes through Flemish fields and cobbles, which led him to seven World Championships and the heart of all Flandrians.

That was Erik De Vlaeminck performing those mystifying parlour tricks on his bike. That was how the best riders trained to be the best bike handlers in the world. And this is how 15-year-old Ben Berden was exposed to his future: cyclocross.

The Beginning.

Ben Berden was born on September 29th, 1975 and lived his early years in Stevoort, a small village near the city of Hasselt. The city lies in Belgium’s Limburg region, where the hills are longer like those found in the Ardennes and where the local dialect drops the ‘n’ off everything: Ben Berde’, Erwin Vervecke’. Think of it as southern twang.

Ben grew up a farmer’s son. A horse farmer’s son, to be accurate. They raised stallions, eventually moving to a larger farm where they could make money by providing stallion boarding and riding lessons.

Ben Berden: When I was little, there wasn’t much sport for me. Certainly not bike racing, believe it or not, as it wasn’t really popular in my area. I didn’t know who De Vlaeminck was. Heard of Merckx of course, but no posters on the wall of bike racers or soccer stars. If anything, I wanted to be a motocrosser. But my dad knew I would kill myself. So I knew it wasn’t in my plan to be the next Everts or Geboers.

Digging holes was, however, a pastime. Holes like every kid was digging around the world. Ben caught the early bug of BMX. Never racing, just riding and jumping, digging those holes to get bigger and bigger air. It was the genesis of his joy of bike riding.

BB: When I was like 14 or so, a relative of mine who was into bike racing saw me riding the BMX bikes around and said, “You should really come ride with me and the club.” So I did and went on like a 40km ride with them. I felt pretty good. It was all pretty natural for me. I was on this 49cm bike with the seat slammed to the top tube. I was tiny, but I hung on to them.”

By the time he was 15, the tiny Ben Berden, 5ft 5in and 100lbs when wet, showed up to try his first kermesse. Riding with the club was not exactly riding a kermesse.

BB: I showed up and these kids were huge! I said, “Where are the juniors?” and they were right in front of me. Like grown men. From the gunshot, I was dropped in the first corner.

Sweet Sixteen.

With enough flogging around the paved and cobbled roads of Limburg, Ben had a flyer put in his hand for a local ‘cross series. It looked interesting, as he was told it had some elements of dirt in it.

BB: It was like mountain biking, I was told, which interested me, but kids in Belgium can’t race mountain bikes until they are like 18. So that was never an option for me, so this was the next closest kind of thing.

He had early successes when he pinned numbers on his back, as he honestly drove better in the mud and technical elements of ‘cross.

BB: I always felt like I could turn better and get through the sand better. But I honestly didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t know how to train, and just used what I learned jumping BMX bikes and it worked. It was really fun. I wasn’t getting killed as bad as in the kermesses, and grinding through sand was fun. I wanted to go faster.

The Formative Years.

His late teens into early twenties saw Ben get the taste for becoming an endurance athlete. His training evolved from simple running loops and long rides, which was all he needed as a junior, to more advanced training and specificity for ‘cross.

BB: I was winning many of the local series year after year. It was very fun and I really felt that this could be it for me. At that time in the early ‘90s we were seeing that it was a real thing to become a professional cyclocrosser. It wasn’t just a winter thing where the road guys would keep up intensity. It was really something we could get paid for. I was already in. I guess I had to. There wasn’t a lot of option for me otherwise.

The promising juniors and belofte (beloften: defined as ‘promises’ in Flemish, or generally riders under the age of 23 likely to become professional) would often get selected to go and ride in exhibition races before the country’s biggest cyclocross event, the Super Prestige, where on ‘any given Sunday’ Flanders’ fields are lined with tape and crowded with 20- to 50,000 spectators, all of whom pay entry to come, drink, smoke, hear music and watch the spectacle.

BB: At one of these exhibition races a few of us got spotted and someone found and talked to my dad about bringing me to a regular set of practices with Erik De Vlaeminck. Problem was it was all the way across the country. Yeah, it’s only like two or three hours across Belgium, but my dad did it for me. Drive me there and back each time to help me get this chance.

Going to these practices, what he witnessed and learned was all new. The training, the discipline, the culture.

BB: It was all just so weird at first. It wasn’t real training to me at first: Erik laying his bike down and getting up while in the pedals. Erik taking all of our bikes and piling them up on each other and telling us to go run to them and find them and get on and sprint. Erik teaching us really how to ride the sand with like one bar of pressure in your tire. Oh, and tubulars. He taught us tubulars. Before then we just rode these tiny little clincher tires. Now we had to glue these things on but it was very clear what they could do.

He was now in the hornet’s nest; the inner circle of this crew of passionate cyclocrossers, among the elite and the rising generation of ‘promises.’

Ascension.

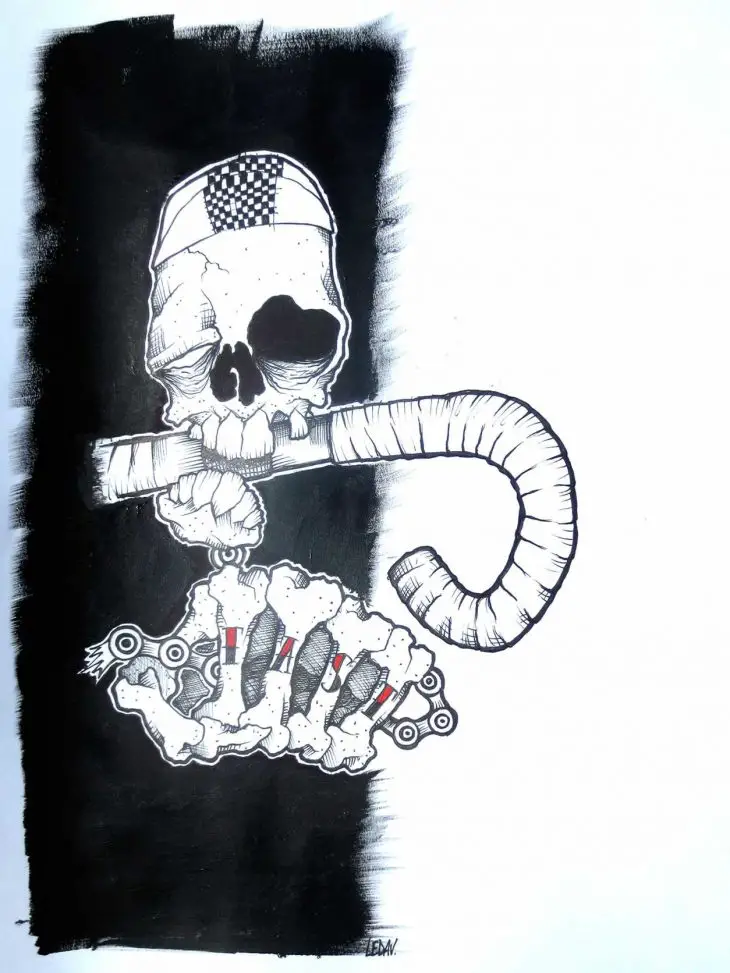

In his early twenties Ben was committed to the life of being a professional athlete. He was rising and becoming more widely known with the various regional results he was ticking off. This was the pre-tattooed Ben, still a character in the making. Earrings, a raw attitude and clearly a stand-out against the sunken faced, track-suit wearing, die-cut bike racers that were his contemporaries. He was carving his own path.

BB: I made an effort to try and be a road racer. The big money was there and I knew I could do ‘cross too for fun, but I learned fairly quickly my whole body wasn’t ready or maybe suited for that. Stage races nearly killed me, and I’d be off the back in the first couple of days. Kermesses were OK, but there was no money really there. So I made a decision to just be a cyclocrosser.

His ascent season after season was noticed. After successful U23 campaigns, culminating with a silver medal at the Belgian National U23 Championships, it was time to move into the ranks of the paid professionals. He’d made it, at least to his first contract as a stagiere with Palmans-Ideal.

BB: I was living it. I did what everyone said. The trainers, the coaches. I learned how to lose some weight by eating certain things. I trained harder. I never drank. I was like a monk and went to bed at 9:00pm.

The results materialized with this type of discipline to the lifestyle. His life was shaping up exactly on plan. Exactly as he wanted it as a professional cyclocrosser: results in bigger races; improved contracts commensurate with his rising talent; interviews with Sporza; mobile homes; team support; a love life. It was a clear future.

BB: By 2004 or so I was on the team of John Saey and Ronny Deschacht. The team had a ton of support and was well-financed. I was now at a level where I was racing with the big names. I was becoming more known. Each race there would be two or three busloads of people coming to see and support me. The money was getting bigger. ‘Ben, win a Super Prestige and there is a 15,000EUR bonus.’ ‘Ben, get selected for the Belgian National team and win the worlds and there will be 75,000 more.’ This was it.

Reaching Higher.

If the math was right, he could train, bank on these winnings and have enough to retire with. Money for property and then on to those cushy gigs the ex-racers got when they hung up their wheels to help with a bit more income. This was the playbook. Just more work to do.

BB: I was always close. Those few seasons, on bread and water, I was always there. Second, third; always really close. I was training like an animal, hours behind the moto. Bed at 9.00pm. Sacrifices. I didn’t know how I was going to win one of those bonuses or a number of them. The team was so supportive and gave me a lot of encouragement. The fans were still coming in the buses every Sunday. That’s when I went on my own to find a doctor to help me.

He found his helper. The doctor told Ben he could get him five or six seconds each lap. He said it would be undetectable if he followed the plan. It was the line. Ben crossed it.

BB: I did this. There’s nothing to say. No excuses. It’s a high-pressure kind of life, and lots of people would have walked away. But I wanted it and I went over that line to get those five seconds.

The results came. Selections to the Belgian National team. Podium appearances. Victories. Contract extensions. Then in December of 2004, Ben returned a positive for EPO at the doping control in Essen. He didn’t hesitate. He admitted his use. Some say it wasn’t remorseful enough of an admission. Most wanted him to just go away.

The Belgian Federation suspended him for the term of 16 months. The UCI investigated and countered the decision by extending to 24 months. The time penalty would likely end his career permanently, but the blood boosting never gave him the results to yield those bonus Euros he so badly desired. Instead, he now faced an uncertain path on how to pay down the 60,000EUR fine.

For the first eight months, Ben could count on two hands the times he left the house. The depression that ensued was symptomatic of guilt, failure and an uncertain path forward. His marriage was now showing cracks. The house of cards quite literally had fallen.

BB: I never left the house. There was no reason to see anyone. I fell into the cave and ate poorly, drank to excess all the time. Trying to pay this debt and all the legal stuff was killing me.

The nightmare he created for himself got worse. Accusations of him being the center of a doping ring, paying lawyers to defend him. Ultimately, the phone taps and DNA evidence cleared him of any of those claims. He did all this by himself. To himself.

BB: My friends rescued me. They slowly got me out of this cave. I finally decided to get a job or two to help pay all this stuff back. I went and found jobs. I was a roof tiler and I worked at the mail office.

Back in the Saddle.

The labor-intensive jobs did three things: got Ben out of the house on a regular basis, paid down the debts that were mounting and allowed him to ride his bike.

BB: One day I walked out of the house to go to work past a bike in my garage. I filled up the tyres and rode. Just rode. I’d get off work very early after working late shifts and had time. It helped me get out. First an hour ride. Then three. Then six. The hunger to go fast was still there. I was thinking a lot when I would ride and it all helped.

Nearing the end of the suspension period in 2007/2008, it was clear Ben was changed. He loved riding his bike again, but knew his limits. He was enjoying life more again as he clawed his way back to a healthier and fitter lifestyle.

Ben began racing again. The new, and increasingly tattooed, Ben was showing some new and unique value; or so it seemed to a Belgian internet entrepreneur, who recognized a marketing opportunity. He hired Ben post-suspension to race, but mainly to talk with VIP clients at the big events.

That was the problem: the big events.

No one likes a cheat, and this is exacerbated by the raucous atmosphere of races with tens of thousands of passionate and highly-inebriated fans. Now Ben was being paid to get back in the ring. Results weren’t as important for Ben’s new team as his was a marketing play, but the insults, beer in the face, shoves and finger pointing took their toll.

BB: The big races… scared me. I was trying to come back into this scene, I was really remembering how I loved to race, but I knew within the first few races this wasn’t for me any longer. This whole scene was not what I wanted.

Ben began to focus on smaller events. Less visibility, often limited TV coverage and he was getting his ass kicked, still.

BB: I was 8th, 9th, 10th every race. Switzerland, Italy, France. Smaller races. Just getting killed. But I loved it. It really was fun. No big tents, not a lot of fans. Just racing.

Coming to America.

The Cross Vegas experience changed Ben. He saw a culture and scene in the US that was more ‘him’. The connection and thoughts remained as he returned to Belgium and continued on with his life. A life that by every definition was eroding. Home life, racing opportunities. It all seemed unwinnable.

David Alvarez was the connection; the link back to the US. An American ex-pat living in Belgium, he had grand ideas for his marketing his fledgling brand, Stoemper Bikes.

David Alvarez: When we launched Stoemper, we wanted to do something bold, and we had the idea to bring a Belgian pro over to race in the US for a full season. I had known Ben for a few years, and he was always a humble and hard-working guy. Moreover, he was a real ‘stoemper’ – running a single ring 42, and excelling on courses with heavy sand or heavy mud. And of course, the heavy metal. Ben was in a place with his career where it made sense for him to come and try something new.

They made the connection, agreements were made and they’d do this together. The idea was for Ben to race in the unique kit and colorful aluminium bikes in Belgium, with a few trips to the US to start to expose the brand there in top races as well.

BB: David was able to help get me to the US. I was going to do one or two races, but I ended up staying the whole time. For the whole season.

A patchwork of guest housing and a full-blown exposure to the US had Ben convinced that this was for him.

BB: I had not felt this relaxed since I was young. The races were so fun. Small. Everyone cheering. I could have a beer the night before a race with other racers, and it was OK. No one spat at me or threw beer in my face. I was competitive and won a few, but it was real racing again.

During this time, Ben landed in Boulder, Colorado. He was placed in guest housing with multi-time National and Master’s World Champion Pete Webber.

BB: I was able to stay with Pete and Sally and their daughter for a long time. There in Boulder, it was a huge scene of bike racers. We all rode together. Did training races. In Belgium, that would never happen! No one trains together. Not like that, as everyone’s got to hide their training.

During this time, these training rides often took Ben on the well-known and scenic dirt roads in and around Boulder County.

BB: On one of the early times there in Boulder, the crew took me out on these dirt roads. I was like, ‘dirt roads?’ But then I saw them. Like pavement and really quiet. It was like an adventure each ride. Getting lost. It was, I guess, my first gravel ride.

A New Life.

The strain had finally come to a head with his life back in Belgium. Ben’s marriage and family life succumbed to an unfortunate divorce, and it was clear that there was no turning back. He was becoming more deeply entrenched in the US, with its culture, its people and with a clear path toward his future. What he needed was solidity. In part financial, and in part with his soul.

BB: I was able to meet and work with Donn Kellogg who believed in me. He was building up Clément and wanted to do it with a real team. He was able to sign me and I could have a new job and establish myself here.

Donn was in the throes of building his start-up. In Clément he was reviving an historic brand of tires that would be brought back to life in new and advanced ways, to satisfy new burgeoning markets: cyclocross and gravel riding.

Donn Kellogg: I was just finishing a European trip to establish our tubular production and was able to meet Ben at a barbecue in his hometown. It was clear to me that I was in front of a man who had made a mistake in the past, took full responsibility for it immediately and was looking for a path back to his professional life after forfeiting his entire life savings. Proud, strong and humble. His candor and demeanor impressed me and with a strong personal recommendation from Brook Watts I decided to start what is now a three-year collaboration with Ben.

During this time two similar lives were beginning their intersection. Ben had been introduced to former professional downhiller and recent cyclocross convert, Nicole Duke. Nicole was turning heads in the local cyclocross racing scene by coming out of nowhere and detonating local Elite women’s fields.

Nicole Duke: I’d just had my second baby and really needed something. I was a bike racer… just loved riding. Cyclocross was incredibly fun and I could train for it while balancing being a mom. I won a few local races and ended up winning the Master’s Cross Nationals a year or two when I came back to bike racing.

The similarities to Ben’s world were deeply parallel in this period. Nicole’s marriage was in the process of unwinding, and they both were seeking joy in some way. If not through love, then through bikes.

BB: We met at the Tusher in the Cusher [event] a few years ago. I knew we were both going through things after a few talks we had. But I knew there was a mix there. Like chemistry. I also knew we were both stubborn!

During this period, Ben made his base in Boulder. Through the connections of the small world of cyclocross, he would take on Amy Dombroski’s apartment. Her new contract with the Telnet-Fidea team had her living and training in Belgium, and freed up a place for Ben to call home in the US.

BB: I was in Amy’s old place, and Nicole and I spent a lot of time [together] when I was in Boulder that summer. I told her she should really go and try for the pro contract with Raleigh who I was now riding with. It was a ‘winner takes it all’ race in Deer Valley in Utah. She won it.

Now both on the same team, Ben and Nicole went into the 2012 season in the same kit, spending ample time together on the road. Learning each other’s nuances and finding a partner in each other.

ND: We both found each other at a time that we needed a partner. We both love riding bikes. We both do not want complicated lives. We like to travel, pack the van and explore.

Here and Now.

Ben’s presence is now part of the regular fabric of America’s highest caliber races. His perennially embrocated and tattooed legs are always available for a chat. He’s approachable and is equally refreshed by the people here. He has found his home.

BB: Race in Belgium again? No, never again. No more big races. Maybe some small ones when I go back over. I don’t want any involvement in that hype. Besides, you have to have a motorhome now to be taken seriously over there. No more. It’s here now. Having a beer after a race and not hiding in a trailer. This is more for me.

Donn Kellogg: When Ben arrives at a race or a ride, he is ready, he has done the training or, in case of brand ambassador work, he is super approachable. He is absolutely wonderful with children.

Ben’s abilities are well-balanced here among the Elite in the US. Consistent podiums and victories show he is in the mix and the playing field is well-balanced. Ben’s timing with the explosion in dirt road racing could not have been better as well. His newfound love of adventure riding is well suited to the new dirt road mega-epics now surfacing.

BB: I never would think about riding a dirt road until I went out with that Boulder crew. It really is an adventure every time. And now these gravel races… I get to push my body differently than I ever have. Five hours and 20 minutes in Chino, over a hundred miles. Absolutely crushed. And even with 1,300 racers, you have to be professional and go as hard as you can. It’s not a tour.

The Future.

Boulder is now home for Ben. His life with Nicole is defined by trust, understanding of similar pasts, a love for bikes and adventure. The future is interesting, and is a major part of his thoughts, while trying to stay in the present moment with his new life.

BB: Five years from now? It’s not clear. Bike racing is all I’ve ever known. My body is good, but this will not go on forever. I’ve been racing as a professional since I was 20, so yes, I am thinking a lot about what’s next.

He and Nicole are beginning to chart their respective courses as professionals, and as a couple. From working with various junior cycling organizations to contemplating business ideas on how to weave in lifestyle into their future, they are a singular unit.

BB: Working with younger riders is very interesting. It should be about adventure for them. I see the power meters these kids have now, but getting out on the bike, getting lost, running out of food… They need to learn their limits. Learn to suffer a bit. Cry and find their way home. Really see if they like this.

As they head in to this next phase of life and career, Ben and Nicole define home as wherever they are together. They have confidence in the future, as they have confidence in what they both bring to each other. Not before long, Ben may be the old rider, attracting the attention of kids on the beach as he demonstrates falling over on his side and magically arising. Demonstrating the adventurous side of the sport.