TLDR: I love this book, and I want you to read it. ‘The Trespasser’s Companion – A field guide to reclaiming what is already ours’, is a call to reconnect with nature. Through a series of compelling essays and case studies, the book illustrates how we have lost our right to access much of the country we live in (specifically, England), and how that has led us to become distanced – or excluded – from nature. As the gap in our knowledge, understanding and experience grows, we lose the powerful physical and mental health benefits that we get from time spent outdoors. With that, we also lose our connection to the land, making us worse at protecting it. To top it all off, all this loss for the many is for the benefit of a very few, often disguised as being in the interests of nature, but when you scratch the surface that argument rarely holds water.

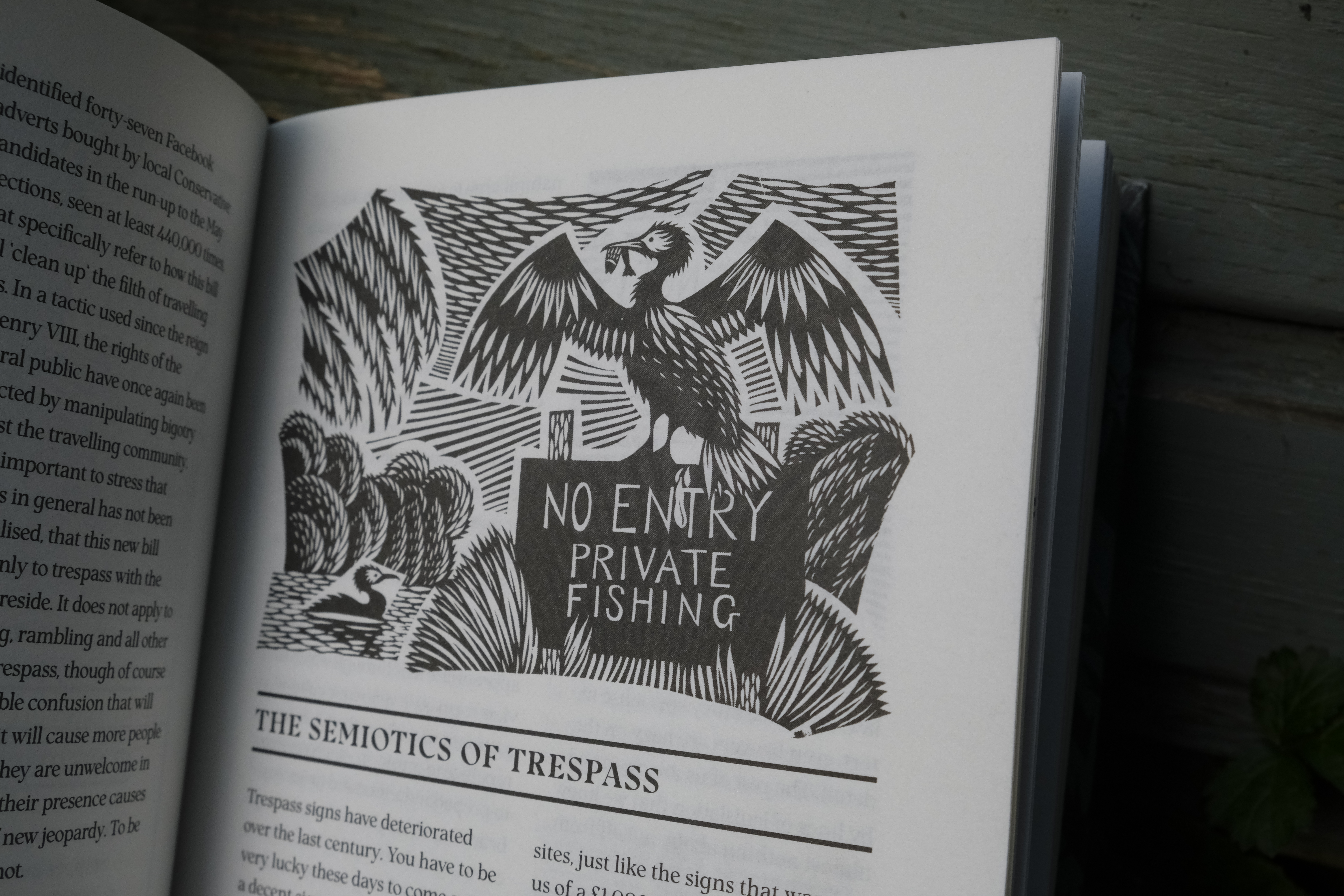

Phew. That all sound like rather a lot. And it is, but the ‘field guide’ nature of the book breaks in down into digestible chunks, complete with websites for further reading, and options for suggested actions or activities. It’s a complete curriculum, covering everything from the social history and politics of land ownership and access, to ecology, dog poo, citizen science, responsible access, litter, and folklore. Teachers could do an awful lot worse than structure a whole school term – or year – around looking at each chapter in some depth, and following the tendrils of possibility that each raises. It’s beautifully illustrated, and the illustrations break up the dense quantity of ideas and information in the book, giving you a space to pause, look and digest – just as you might pause on a walk to take in the view.

However, much as I think this is a great book that you should definitely read, I feel that it has some shortcomings. Firstly, there’s so much information in there, I wanted to go back and reference it, or read a bit again, and the infuriating lack of an index makes that very difficult. Please can we have an index in the second edition?

On to more debatable critiques – and bear in mind that they’re ones which I make because I want as many people as possible to read this book, because I think the subject is so important, and the execution is by and large excellent. While I appreciate being more informed about access rights – and reading about different angles and arguments in favour of increased access to the countryside is useful and interesting – it’s preaching to the converted. Arming me with more information to help me argue the case – and hopefully take action – for increased access is great, but I feel that it might have been more powerful if a greater effort had been made to engage the middle ground, the political centre, and maybe even a few Tory voters and Telegraph readers.

Join our mailing list to receive Singletrack editorial wisdom directly in your inbox.

Each newsletter is headed up by an exclusive editorial from our team and includes stories and news you don’t want to miss.

Yes, I get that it can be difficult to keep the politics out of something you feel passionately about when there’s a self-serving corrupt government passing laws that place restrictions on our civil liberties that might be more at home in a dictatorship…see? But while there is a lot of useful discussion of the history of common land, lack of inclusive access to the countryside – or disproportionate exclusion – for various groups, I think the overall tone is one that speaks to the political left, the hippies, the people who are likely to have been doing No Mow May before it became fashionable. I want those who might not be first in the queue to jump a fence or ignore that ‘Private’ sign to pick this book up and read it to the end.

The short section on farmers is relatively sympathetic, and contains the shocking statistic that one small farmer a week is lost to suicide. I would have liked to read a bit more perspective from the farming community to perhaps gain some insight as to how increased access could be achieved alongside modern farming methods. I’d like to know what motivates some farmers to make access – sometimes even legal access – difficult, and perhaps whether there are ways I could behave – or spend – that would mitigate that.

Perhaps such a chapter would have helped create an ‘us and them’ where the ‘them’ was the offshore owners and landed gentry, and the ‘us’ included a few more Worried of Suffolks and Farmer Jones of the Yorkshire Wolds. As it is, I feel like the book preaches to the choir and misses an opportunity to give the sales pitch to a broader market. There are plenty of middle class Conservative voters out there who would pick one nursery or school over another because it offers their little darlings a Forest School session for an hour or two a week. Why not try to bring them into the readership, and make them think that the benefits of Forest School could be available to them at evenings and weekends too? The horse riding lobby may feel a long way from the activist conservationists or lost traditional commons rights, but most horse riders are largely confined to bridleways. Yet there’s barely a mention of horses, save for in conjunction with hunting. Could we not get the non-hunting horse riders interested in access? Similarly, there are surely plenty of Telegraph readers that like a walk, some bird spotting and a touch of rural idyll that would be glad of being able to explore a bit of land that’s currently marked private and fenced off for the benefit of an Oligarch.

To quote the late Labour MP, Jo Cox, I suspect we have more in common than which divides us, and I would have liked to see this book speak to a wider audience. Unlike its predecessor ‘The Book of Trespass’, which goes more deeply into the history of land ownership in England, this is a book specifically designed to turn thought into action to bring about change. The message is too important – and the power of the landowners too great – to miss out on any potential support.

There are a lot of facets to the message that we need to reconnect with the land and reclaim our right to it. The Trespasser’s Companion sets out the context: why we need nature, the current law on trespass, the historic rights that we’ve lost (or forgotten). But then it goes beyond that – which is covered in much greater depth in ‘The Book of Trespass’, also by Nick Hayes – and moves into ‘how’. Much is made of the responsibilities we have as stewards and users of the land, of the need to understand how nature works, and to educate people on how to access nature without disrupting it.

Perhaps problematically for mountain bikers, there’s a strong emphasis on the ‘leave no trace’ or ‘leave a positive’ trace version of access. One or two bikes riding across a field can probably manage this, but the reality is that many of us would like to ride the same wiggly line down a hillside, perhaps with a catch berm or two dug in. That’s not a leave no trace proposition, but does that mean that it’s wrong? The book doesn’t really address this: is it more important to connect with nature and accept that some bluebells may get trampled; or is leaving the nature undisturbed key? Is walking – or canoeing – the only permissible fun, because they’re the only activities that leave no trace? How about the trace left as you drive your canoe to the river, or your family out of town to the foothills? Is that better or worse than the rider who rides from home but rides in some ruts as they do so? I’d have liked to have seen a chapter discussing the balancing act of access and impact, with a little less of a romantic ‘wandering gently among the trees, making sketches and listening to the birds’ hue to the types of activities we might expect people to do in our green spaces. On the other side of that coin, I’d also have been curious to read about views on the value – or not – of having protected areas where no humans are allowed to access, intervene or profit, and nature is truly left to its own devices (rather than landowners being left to their own devices, which is more the case at present).

If the editors felt the need to create space for all these extra chapters I’m suggesting, I think that the end the book left some of its strongest and clearest arguments behind and introduced elements of fairly fanciful thinking that, while laudable, might be best kept to late night campfire discussions among likeminded folks who’ve also had a drink too many. I don’t think everything needs to be black and white and totally scientific, but I think the book would be stronger if it had left out some of the more ‘spiritual’ arguments. Rituals and sawaldeor (a sort of spirit-animal concept) felt a bit woolly and clutching at straws compared to other points made in the book – and I think could turn off the audience that needs to be converted. Likewise, it’s not that democracy isn’t broken, but it seemed to me like too big a concept to jam into a short chapter at the end of a book, and one which is something of a potential distraction from what are other core messages around which many people could unite.

Overall

All that said, there is heaps of useful and interesting information in this book and it’s beautifully presented. It’s engaging and convincing, and it makes it feel as though change is possible. There are lots of tiny steps you can take, and some bigger ones too. I doubt anyone – no matter how much of a flower-sniffing badger-tickling tree-hugger you might think you are – can read this without finding sections that don’t spawn new ideas, or give pause to think differently about a situation. There are practical suggestions for better stewardship of our environment, activism activities you can put into practice, and even apps you can add to your phone to add citizen science to your daily life. You’ll be armed with arguments against the many reasons we’re told we should stick to the path, or can’t go here, or can’t swim there. You may well be emboldened to go out and go somewhere new and off limits. It’s an incitement and invitation to trespass, but to do so with thought and purpose.

92% of English land and 97% of English rivers are out of bounds to the public. Eleven million people live in areas with less than nine square metres of public green space per person. Half of England belongs to just 1% of the population, and each of that 1% owns an average of 10,600 acres each. If these figures make you want to get mad, or even, then this is the book for you.

While you’re here, you may also like to read this:

Review Info

| Brand: | The Trespasser's Companion |

| Product: | Book |

| From: | www.bloomsbury.com/ |

| Price: | £14.99 |

| Tested: | by Hannah for |

Home › Forums › The Trespasser’s Companion – A field guide to reclaiming what is already ours

The topic ‘The Trespasser’s Companion – A field guide to reclaiming what is already ours’ is closed to new replies.

Spread the word:

Spread the word: