The mere mention of homeopathy is enough to send certain individuals into paroxysms of rage. So why is it still so popular – and what does it have to do with bikes?

In my first column for Singletrack, I asked everyone to think carefully about whether we really need to purchase that new item of kit.

Shortly after its publication, a gang of thugs hired by a powerful cabal of online retailers broke into our house, beat me up and took our cat hostage. So for this one I’m going to write about why it’s sometimes good to buy stuff without thinking it through.

We all know about the bike industry and the way it spills out dubious claims like ‘Fast and Furious’ sequels – 30% lighter, 70% stiffer, 110% less scientific… Carbon parts that weigh the same or more as aluminium ones. Frames that 60 different people have worked on (mmm, sounds fingerprinty). Claims of stiffness that might be relevant if they were applied to helicopter blades, rather than something propelled by your limp little legs. Made-up names for materials (‘Unobtainium’, anyone?). You get the idea. Why do people buy this stuff, and sincerely claim it makes them a better rider?

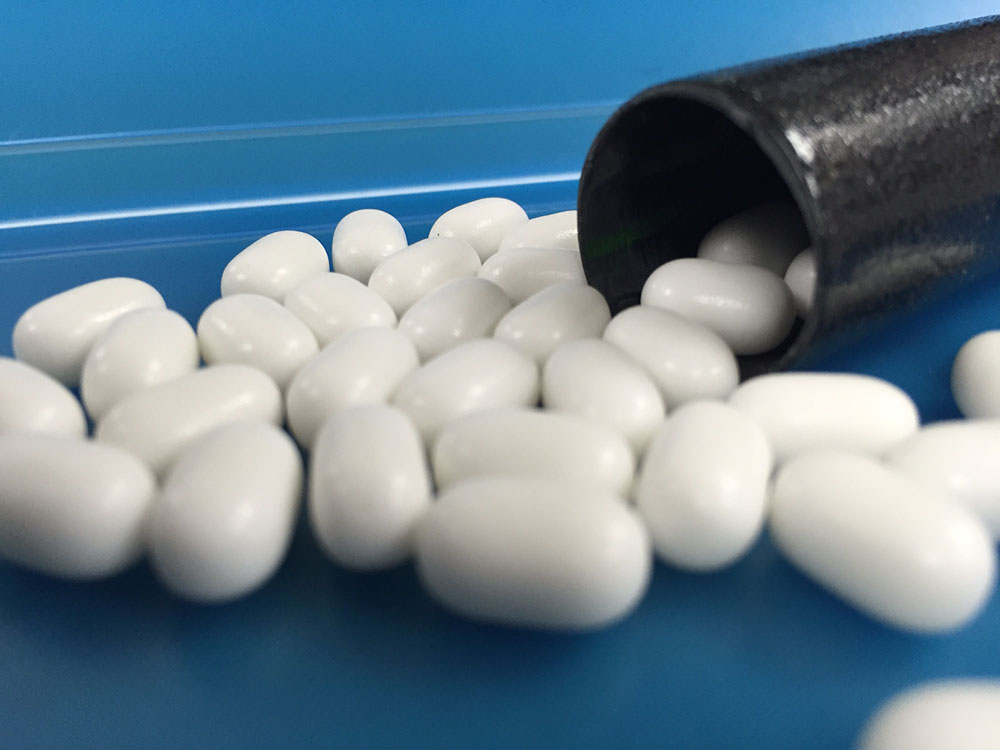

Let’s try a little thought experiment. Imagine you’re ill. Not ill in a four-pints-plus-too-many-whiskies, nothing-a-fryup-can’t-cure way, but worryingly, persistently, indefinitely ill. Doctors are unable to diagnose what’s wrong with you, but eventually you’re invited to take part in a medical trial, and a man in a white coat gives you a course of pills which – over time – make you better. What you don’t know is that there’s nothing in the pills apart from sugar and a bit of food colouring. They have no active ingredients, but they still work.

This isn’t an example I’ve just made up, it’s a measurable, repeatable phenomenon: the placebo effect. And it applies to more than just medicine.

Mountain biking, like anything with a human at the controls, is not just a game of numbers. I remember a definite ‘level up’ moment from early on in my mountain biking experience: a flight of shallow steps near my house that I’d been trying to ride up. Never a natural at even the most 8-bit technical terrain, they were defeating me every time. But then I got a new set of suspension forks, and on their maiden voyage I managed to clean the entire stack of smug right-angled gits. Achievement unlocked: stair master.

A couple of weeks later, I saw someone successfully negotiate the same steps on a tatty old touring bike with drop handlebars. To all but the most addled observer, this suggests that it was more about the rider than the equipment. Yet if someone had swapped my mountain bike for his Dawes Galaxy, I doubt that I would have been able to ride those steps on it, no matter how many times its stable touring geometry, 32mm tyre clearance and full mudguard and pannier mounts were pointed out to me.

We all have that moment where a new bike or tyre gives us a big old confidence boost. A spot of bike maintenance can also have the same effect. A friend was waxing lyrical about the feeling when everything’s “nailed together tightly” with nary a creak or clunk to be heard, and I know what he means. Sam Hill rose to the top of downhill under the auspices of mechanic Jacy Shumilak, who’d fill parts of his frame with foam, or use self-adhesive Velcro to silence rattles. (New parents, why not try this technique on an annoying baby?) With his distraction-free Iron Horse, on his inefficient flat pedals, Sam schooled the world’s best riders. Sure he was gifted, but just as importantly, he seemed to be surfing over the most technical tracks on a wave of complete confidence.

By now, like the angry mob in The Simpsons, you’re probably all crying: “Give us some of those placebos!” But it’s not all good. If unimportant things can make a positive difference, it follows they can have a negative effect, and the placebo effect has its ugly cousin: the nocebo effect. The ever-changing parade of preferred tyres is a good example of this: anyone still running Conti Vertical Pros? Continental still makes them, and they were good enough for everyone ten years ago, so why not now? Another World Cup mechanic, this time on the cross-country side of things, recounted tales of fussy racers who insisted that their saddles were at the wrong angle, despite being set up perfectly last time they rode. His solution was the sort of pragmatic genius that will be familiar to anyone who cares for a stubborn toddler – he’d adjust the offending saddle, then change it back when they weren’t looking.

There are also limits to the placebo’s power. That 350g helmet you don religiously before every ride wasn’t designed to protect you against a 15ft fall, or a crash at 30mph. If it was, it’d be twice the bulk, four times the weight, and sat in your wardrobe next to your motorbike leathers. On a World Cup downhill track, where you can break a leg if you overshoot the landing of a jump, relying on some beefed-up leg warmers to see you through is probably going to end badly. And yet I also doubt the men and women pushing the limits of the sport would be doing much pushing at all if they didn’t have a fair degree of confidence in their kit. Instead they’d probably be on internet forums complaining about their tyres.

Back to medicine, briefly. Some doctors, including quackery’s arch-nemesis Ben Goldacre, argued for “alternative therapies” – those sugary pills, or an equivalent – to be more widely available, alongside conventional medical treatment. The reasoning is that although they shouldn’t work, they sometimes do, often where conventional medicines fail. So delivering some in-house woo, at a reasonable cost, can save the NHS a substantial amount of money. So too with riding: if you want a bit more enjoyment and confidence, that shiny anodised part can bring both. There’s absolutely no guarantee it’ll work, but at least you’re not giving your money to a homeopath.

The placebo effect is funny like that – the workings may be nonsensical, but the benefits are real. Or to put it another way: if you’re suffering from an imaginary ailment, you probably need an imaginary cure. Preferably one made out of carbon.