From the Archives – Singletrack Issue 15 – 2004

Words Craig Woodhouse & James ‘Crazylegs’ Lyon | Pics Crazylegs and Keswick Mountain Rescue

We’ve all had epic rides that have ended in the dark. Or ones with a near casualty, a near miss, or with a broken, but just-fixable bike. Sometimes, though, luck isn’t on your side and the seriousness and remoteness of your situation is brought into sharp focus. What happens then?

The Casualty

Only a short descent, then a climb back out. It looks simple enough, but I know I’m going to struggle to get down… still, I’m pretty sure, once at the bottom; I can make the climb back up. OK, weight tentatively forward, over the top step, trying not to set off into an uncontrolled, over the front cartwheel. I’m desperate for grip on my left, but it’s not really there, pinching the bar between my left thumb and forefinger, desperately trying to apply the brakes to control my descent. The ground is stepped evenly, but I feel like I’m flailing. It’s a test, a personal test more than anything… and I feel like I’m going to fail. I lean heavily to the right, the muscles on my side left bunch to compensate, I drop my left knee. Despite the cocktail of painkillers I took earlier, it still really hurts. Wince, recover, and prepare for the next move, repeat. It’s only a short descent, but it seems to take an age.

Finally at the bottom, I teeter round in a tight U turn. Despite the relief that I’ve made it to the bottom in one piece, my earlier confidence that I’d clean the climb rapidly dwindles. Breathe, go. I push down with my right hand, tense, balance, then push up the climb, left leg powering down. Grunt, easy, we’re off! I clear the next step. I’m going to make it! I’m pulling my left elbow into my side; it seems to make my balance better. A pause part way up, to snatch my breath back, but I’ve not stopped. And a final push to the top – as far as I’m concerned, I’ve cleaned it, first time round. But it’s not my call.

The physio turns to me, “Super, you’ve mastered doing stairs on your crutches, well done, I think we’ll let you go home”.

48 hours earlier I was riding the Borrowdale Bash loop, south of Keswick in the Lakes with James aka ‘Crazy Legs’. I nearly busted my lungs riding up Honister Pass, a 1 in 4 ascent, which I pretty much cleaned on my Spot. But not quite. I didn’t push, but when my world went a little black, I figured it was time to stop and take in some air. Annoyingly, it was after the worst of it, but I was just too knackered (read weak) to top out. When we turned to start the descent, I was still shaking a little. A kilometre and a half of rolling single track leads you to a wide rocky descent. James points out where Ben twisted his ankle on their previous trip, before warning me “It’s pretty rough down here in places”. He’s right. I’m skipping merrily down, just about controlling my speed. I’ve been fettling the forks, and they are a tad soft really. I’ve no honest idea how fast I was going, but I’ve gone faster, for sure – it was wet earlier, and we’re not racing. I spy a particularly rough section, feeling the lack of travel at the front; I figure the best course of action is to let off the front brake. In my mind, this will free up some travel in the fork and we’ll roll right through it. I can already see the point where I can scrub the speed back off.

Honestly, I’m not quite sure what happened then. I think the forks bottomed out into a rut, the bars rotated, throwing me over. What I do know is a fist sized rock drove its way into the fleshy part of my right hip, underneath where your arm would naturally hang, below the belt line. I’m not sure if I was still clipped in or not, but the bike rolled over the top of me, before clattering down the hill. I guess I must’ve rolled a bit further, before stopping in a crumpled heap. I shouted, quite loudly (words to the effect of ‘Ouch’).

James was with me pretty quickly. A little shocked, I tried to move, as I was lying on a bed of rocks, pretty sore, and twisted. I think I was head down slope, belly up. I couldn’t. Not sure if it was just a bad ‘dead leg’, I have to get James to rotate me to a more sensible position. I can’t tense any of the muscles on my stomach, both my wrists are knackered, and I realise – most disturbingly – I’ve got no grip in either hand. In three painstaking manoeuvres, barking instructions to James, I get to a relatively comfortable position. My right leg is extremely sensitive; a rotation in the wrong direction is agony. And it needs constant support, which I discover to my painful horror as I fail to support it with my knackered hands mid-manoeuvre.

Two mountain bikers ride by. “You OK guys?”, “Yeah, just taking in the scenery, thanks”. I’m going to get my breath back, then ride this out. “Bike OK, James?”, “Seems to be, but you’ve lost the front brake hose”. Arse. I’ll just have to push her out… maybe I can manage with the rear only… just catch my breath first. James asks if we need to call for help, “No, I’ll be fine.” Ten minutes go by. I’ve still not managed to get up. We’ve been joined by a pair of walkers and I’m getting a chill. Slowly, I realise I’m not going anywhere fast. Perhaps it’s time for help. Again James asks if we should call. Reluctantly, embarrassed at my incompetence to stand up with a dead leg, my inability to ride a simple trail [yeah right – ed], I am forced to agree. We both have mobiles, James has a GPS too. “Keswick mountain rescue will be here in 20”. I feel like a fraud. I hope no one else with a serious problem needs them today.

Another ten minutes later and I’m now secretly rather glad they are coming. Despite a hat from my bag, a loaned fleece and space blanket, I’m cold. And my teeth are chattering uncontrollably. I’m getting intermittent pins and needles in my right side, and both hands. There’s an awful, sickening moment where it feels like my insides have turned into tapioca. Hardly the most frightening of descriptions, but when you’ve not moved for twenty minutes and your not sure what’s up, it’s a pretty awful experience. I guess this is what it feels like to go into shock.

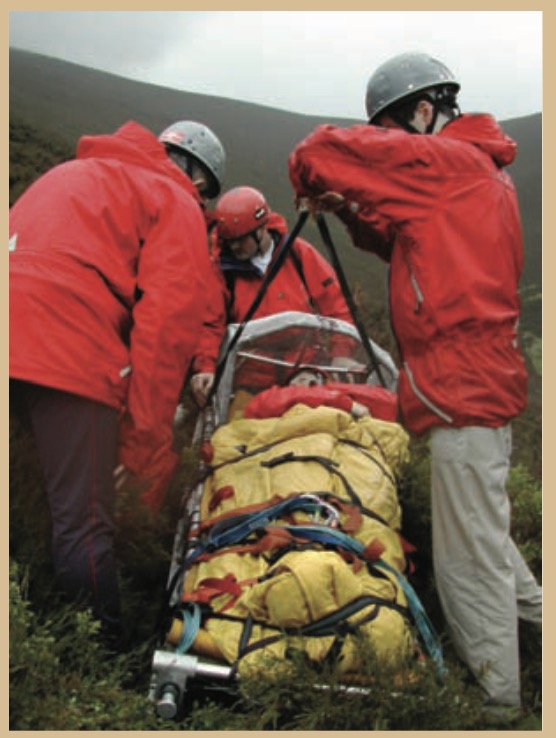

Mountain rescue were excellent, I was amazed to see a Land Rover drive up the descent I hadn’t been able to ride down. How embarrassing. There were more folk than I could count, who quickly had me wrapped up, monitoring my pulse & blood pressure, trying to determine what was wrong. They decided I needed to be taken off in a helicopter, as without fully understanding my injuries, the Land Rover might be too rough. Everyone I’ve spoken to since thinks I’m lucky to have had ridden in a yellow wheelie bird. Honestly? I’d have preferred a window seat. I expected the move from floor to stretcher to be excruciating. Hands hoisted me into an inflatable stretcher, which was pumped solid to fit my twisted form. Thankfully, it was far less painful than I expected. I cannot thank the guys enough, or the person who designed the stretcher as I hardly felt a thing.

At the hospital, stripped naked of my garments with scissors, after X-Rays I’m told I’ve fractures in my hip and a broken bone in my left hand. The latter is a spiral fracture which narrowly avoids being wired up. I’m a very lucky man. The consultant compares my hip to a Polo mint. How often can you crack one side without the whole thing splitting in two? I’ve cracked the iliac crest, which is the ‘wing’ of the hip – the part that would sit above the belt line. Amazingly, I’ve avoided damaging the femur joint, or splitting my pelvic girdle in two. There is a crack snaking its way through towards the sacroiliac joint, but I am told my hips are stable and I should try to get onto crutches.

Transferred to the ward, I don’t move for almost 24 hours. I can’t even slide up and down the bed. The physio arrives and we try to get me out of bed. Grim determination and an over-important sense of self pride has me finally gritting my teeth on the bedside. With a cast on my left, and sprain in my right hand normal crutches are disbanded and I’m given a Zimmer frame. I get no more than a couple of feet before the pain leaves me ready to vomit. I can’t even make it to the bathroom. Finally eased back into the bedside chair, I’m more comfortable than I’ve been for a long time.

The next day I’m determined to get up and moving before the physio arrives. I’ve literally got myself into the Zimmer by the time he arrives. Bonus! Movement is far better today, and I’m provided with a gutter crutch for my left hand (strapping the forearm at 90 degrees, the weight from the upper arm passes straight into the crutch) and a normal crutch for my right. “If you can make it down the steps, you can go home, but I expect you’ll be here for a few days at least”. The afternoon will be my first attempt. Excellent, a challenge.

The Riding Buddy

Falling off your bike badly is never good, but one thing that ranks right up there with it is seeing a friend take a bad tumble. Although you don’t get the pain, you’re now responsible for their welfare, and possibly their life…

Here’s the story from James’s viewpoint…

Craig looked in complete control as he began the rocky descent, heading over a blind crest and into a boulder field with me about ten yards behind him. The next thing I knew, his bike was vertical as Craig went over the bars and landed hard on the rocks, his bike bouncing wildly down the trail and coming to rest 15 feet further on, its front brake hose ripped out of the caliper by the impact.

Craig was yelling in pain, which at least told me he was still conscious. I got to his side and checked him over quickly: no bleeding, no head injury. I recovered his bike and sat with him until he’d got his breath back and stopped swearing.

More miles = More potential for accidents?

Perhaps it’s the increase in popularity of endurance racing. Maybe it’s the feeling of security on man made trails. Or just the comfort of the modern mountain bike. Whatever the reason, more people seem to be riding more often, more miles and in some case more bikes. Unfortunately, that can bring on a greater exposure to risk, seen recently in the number of incidents reported on the Singletrackworld.com forum.

Occasionally these have been down to equipment failure, but most are just plain old rider error. It begs the question, are you prepared for when epics go wrong?

Craig took an unscheduled dismount over the bars in the Lake District, and as a result was evacuated by helicopter. A genuine accident, it seemed like good opportunity to ask Keswick Mountain Rescue, was this rider prepared for a day in the hills?

In this case, Craig scored fairly well. Out with another rider, James Lyon, both riders had mobile phones. James even had a GPS. They had a full complement of spares, water, snacks and even a first aid kit. Not that it was of much use to broken bones in this case. Both were dressed for the weather in leggings & winter jackets, and they even had a spare hat. Realistically, except perhaps a space blanket, there was little else they could have carried. Though it’s worth noting, by the time mountain rescue arrived both casualty and nurse were chilled.

While not wanting to paint a picture of complacency, Keswick Mountain Rescue reported they ‘pull off less mountain bikers than they would expect to’. Despite this, they have recently done training days with the mountain biker in mind, even going so far as to take specific training to safely remove a full face helmet at the local jump spot. And despite this, they only see two or three mountain bike incidents a year.

One of the best things you can carry around is knowledge of basic first aid. Often it’s something you can persuade your employer to pay for, and is useful from the home to the hill. Mark Hodgson, Keswick Mountain Rescue team leader said even though he has three GP’s on a 45 man team, they do not want to be the ‘Holby City’ of the mountainside, patching people up on the mountain; their motto is ‘Grab and go, not stay and play’.

So when is the right time to call mountain rescue? Sooner rather than later. ‘I’d rather turn back en route than arrive too late’ said Mark. With mobile phones it’s far easier to get in touch with the emergency services than ever before (Dial 999 and ask for Mountain Rescue), but that’s no excuse not to prepare for your ride. Maybe you’ve read this far, and there has been no revelation. Which is a good thing, hopefully you are already fully prepared. Sometimes riders do stupid things, but sometimes, we are just riding along and these things do happen, so do your best to be ready. Just in case.

We’re jealous Craig, we really are

I immediately realised that riding the rest of the route was not an option; the initial decision was for us both to get down to Grange then I could ride back to Keswick and get the car. Craig was giving me directions to move him around but each time I moved his leg, his face contorted with pain. I got him as comfortable as possible, managed to get his CamelBak straps off his shoulders, put a warm hat on him and zipped his waterproof up to the chin. Craig still believed that he’d be able to walk in a few moments but this just wasn’t happening. Plan A of ‘hobble-down-to- Grange’ was out, it was time for Plan B of ‘Get-help… NOW’.

I put the call in, giving them our grid reference (God bless the Global Positioning System) and a description of the accident. At that point, two walkers stopped to help, giving us spare fleeces and a space blanket to wrap up a by now shivering and forlorn looking Craig… he was going into shock and things really were becoming serious.

There wasn’t much more I could do except stay with Craig, keeping him warm and talking until the cavalry arrived. The walkers stayed too… we had all their kit for starters so they didn’t really have much choice. Half an hour later the first rescue guy turned up, jogging up the steep rocky slope carrying a small house on his back containing the world’s supply of rescue gear. He wasn’t even out of breath as he arrived, assessed the situation and radioed instructions to the rest of the team who arrived shortly afterwards in a Landie… a seriously impressive bit of 4×4 driving. They got Craig onto oxygen, then Entonox and wrapped him up in heavy thermal blankets. The teamwork was very impressive as they moved him onto a huge stretcher with a vacuum bag t hold him in place. One guy asked which bike was Craig’s. I pointed out the singlespeed and the reply came back, “I don’t want a bike that’s only got one bloody gear!”

The Rescue team suspected that Craig had damaged his hip in some way and didn’t want to move him any more than absolutely necessary. Driving him down was out of the question; the track was way too rocky. One radio call later and an RAF Search & Rescue helicopter was on its way. I heard the last of the radio call, a laconic “Copy that, Search and Rescue on the way, ETA 45 minutes”. Exactly 45 minutes later, the RAF Sea King was landing at the top of the descent into a space most people couldn’t have parked a car in; Craig was put in the back and taken off to Carlisle hospital… he was there in 8 minutes. I got the less comfortable option… they loaded the bikes and all our kit into the Landie and dropped me off where I’d parked my car, I then drove over to Rescue HQ and found that they had jet-washed our bikes for us. “Well, we were cleaning the Landie, it made sense to do the bikes as well.” They made me a cup of coffee and a sandwich and gave me directions to Carlisle hospital. I tried to apologise for having to call them out but they wouldn’t hear of it, saying, “You needed us, we enjoyed doing it and it was a legitimate call out – besides, I think you got me out of cutting the grass.” From the time of the accident to the helicopter landing had been about two hrs. It was 20 minutes before I’d even called out Mountain Rescue and without them we really would have been in trouble. The guys were very professional, very thorough, yet kept a dry sense of humour going right throughout the rescue. Definitely a case of not really appreciating what they do until you need them.

I didn’t have my map with me as Craig had spilt a bottle of water all over it that morning but I know the route very well anyway. I could have described the location accurately but the GPS saved me the trouble. Top bit of kit. We were lucky that we were both wearing heavy-duty clothing and waterproofs as the weather when we set off had been pretty bad. Fortunately by the time of the accident it was quite a nice day although still a bit cold once we stopped moving. Huge thanks go out to the two walkers (Michael Beglin and pal) who gave up their space blanket and spare fleeces until help arrived and thanks to the Keswick Mountain Rescue Team – it would be difficult to imagine a more professional and good-humoured bunch of people.

Craig was unfortunate, but lucky. He crashed in the presence of someone else, on a reasonably well travelled track. He had a helmet (now written off), spare clothes, knew where he was and (probably importantly) was in mobile phone range.

He’s up and about now and just getting back on a bike off road. Although it probably won’t slow him, or any of us, down, we’ll at least be a little more aware of both the potential remoteness of our grimy pastime, and the proximity of potential help.

Join Craig’s dots

Prepared?

Here’s a list of tools, spares and equipment that we would expect people to carry on a selection of rides. It’s not comprehensive, but it’s a place to start, from which you can add other stuff specific to your bike, terrain and the conditions. In all cases, someone else should know where you’re going and roughly when you’re due back, even if you feel silly doing it.

Absolute basic: – ‘The short local ride’

1 Spare tube and repair kit, pump

2 Water

3 Basic Allen keys

4 Phone (or a friend with the above) plus money for a call.

5 Helmet

6 Appropriate clothing for the weather on departure

Standard:- ‘The all dayer’, possibly away from home AKA the modern MTBer

The above plus:

1 Long nosed pliers

2 Adjustable spanner

3 Zip ties & electrical tape

4 Spare brake pads

5 Chain breaker and chain lube

6 Spoke key

7 Basic first aid kit (and know how to use it)

8 Map, compass, (GPS if available)

9 Carry spares in a waterproof bag

10 Space blanket & hat (between the group at least)

11 Extra clothing to anticipate the changeable weather and possible

altitude change e.g. fleece/waterproof.

12 Snacks, meals and/or money for food and known places to buy food.

13 A change of clothes back at the car

14 A friend to ride with

The works: – Epic rides and overnighters like the Polaris, bivvy and bothy trips.

The above plus:

1 Tent or bivvy bag

2 Sleeping mattress

3 24hr food & rations

4 Cooking equipment

5 Sleeping bag

6 Water purification

7 Advanced first aid kit (and someone who knows how to use it)

8 More spare clothes & waterproofs

9 Head Torch and dry matches.

10 Chamois cream

Keswick Mountain Rescue

Keswick Mountain Rescue Team is one of the busiest rescue teams in the country. They cover over 400 square kilometres, three of the highest mountains in England, and one third of the tops mentioned in Wainwright’s Guides. Mountain Rescue Teams are entirely funded by voluntary contributions and all contributions are gratefully received. Details of how to donate can be found at: http://keswickmrt.org.uk/

Great article, only thing I’d add is a slight change to the call for help – if you need them please phone 999 and ask for Police THEN Mountain Rescue.

Alternatively, text REGISTER to 999 and you can even text the emergency services if you don’t have great signal.

It was me that wrote it, that’s me in the red waterproof / silver helmet in the cover pic (although actually when you read that online version, it doesn’t quite flow right; in the magazine there was a sort of sub-section within it outlining some other details but that divide and the continuity of my / Craig’s writing doesn’t carry through into the online version). Also it obviously went through STW’s sub-editors who tidied it up for ease of reading / space etc so maybe not every last detail is captured in there.

I did 999 > Police > Mtn Rescue. When we got put through to them they asked me to describe the location, just to make sure that I’d read them the grid ref numbers correctly. Obviously this was in the days before smartphones and I’m not even sure the 999 text register service existed back then. Still fairly early days of mobiles, I’ll probably have had some sort of brick Nokia thing. I remember I had a GPS device, one of the early ones that used AA batteries and had a small finger cursor button to scroll the map; it was before the days of cycling-specific ones. That’s where I got the grid ref from.

21, nearly 22 years ago that incident! Wow.

Thanks for the response, it was a truly great read!