Now that we’ve moved on from being dicks about wheel size (well, mostly), the new super exciting topic for debate in mountain biking right now would seem to be geometry. Yes, numbers. Having taken over as the focal point for online debates between bike designers and armchair engineers all over the globe, this focus on geometry, and our undying quest to find The Perfect Numbers™, means we’re now programmed to ask questions like; “How uber-slacked out is that bike maaaan?”, “Gurrrl is your reach over 480mm?”, and “Bro! How itty-bitty tight are those damn chainstays?!”.

If you read the online comments sections, it would seem that every person and their dog has developed their own theory on what frame geometry is the best at doing everything. Which of course is impossible, because everything is a compromise. Sorry, but it’s true.

Regardless, that hasn’t stopped those riders who scrutinise numbers on a screen to the nth degree – to the point where half a degree may be sufficient to discredit a particular bike altogether – even if it’s actually a really nice bike to physically ride.

Here’s a thought though; what if the ideal head angle wasn’t a static concept? What if your bike could be altered to change the geometry to suit the riding at hand?

Peter Charnaud isn’t the first person to come up with on-the-fly adjustable geometry. Bionicon is the most infamous brand to offer such on-the-fly adjustability, and suspension manufacturers have offered travel-adjustable shocks and forks that also alter a bike’s dynamic geometry as well as total travel.

Charnauds’ take on the concept however, is no doubt a unique one, and it is neither hydraulic, nor electronic.

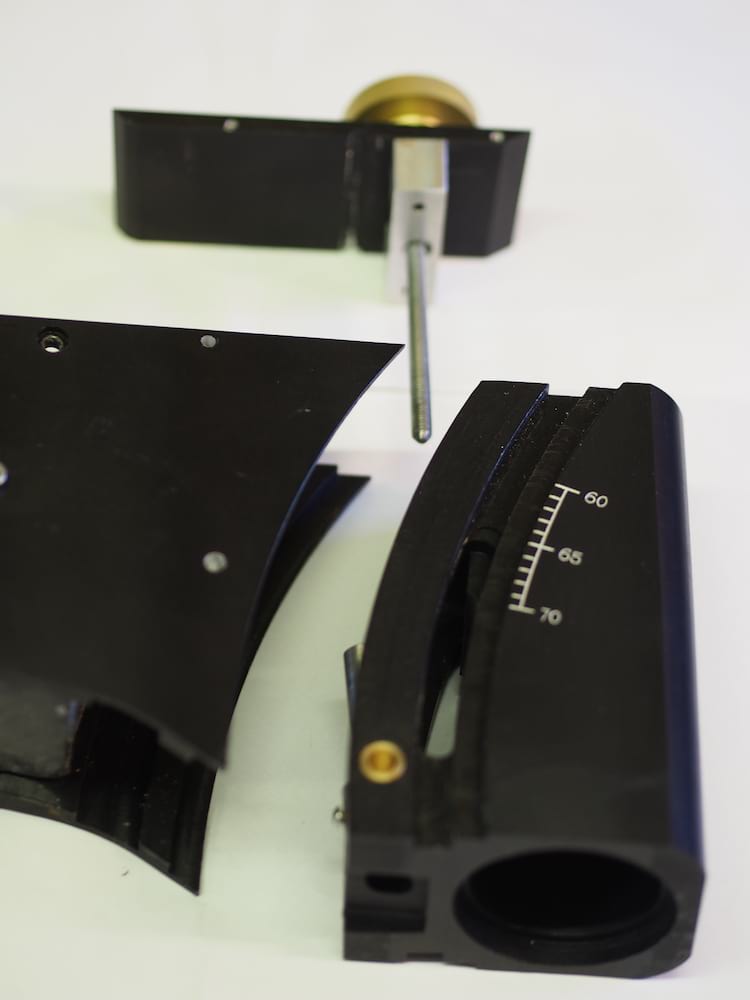

Designed to offer an adjustable head angle that is largely independent to the rest of the bike’s geometry, Charnaud’s Variangle concept is made up of a mechanical two-piece system. There’s an alloy cradle that forms part of the bike’s mainframe, and a separate headstock component that can be rotated independently of the frame. Using a curved and keyed track, the headstock slides up and down in a predetermined arc that allows the head angle to be slackened or steepened.

In addition to the head angle, the Variangle also affects the front centre length and the overall wheelbase length. As the fork slackens out, the front centre length increases to add stability. The general idea being that you want a steeper head angle and short wheelbase for climbing, and a slacker head angle and a longer wheelbase for descending.

In the case of this bike, the head angle can be adjusted between 70° in its steepest setting, and as low as 60° in its slackest setting. To put that into perspective, that is slacker than most World Cup downhill race bikes.

Here’s the word from Charnaud on how the Variangle system works;

“The design of this is such that the virtual pivot point is 225mm in front of the frame and level with the bottom of the headtube. I.e. the effective pivot point is vertically over the front axle. Thus as you change the angle (rotate the headstock angle) you are extending or retracting the headtube enough to keep the bike frame height almost the same. It will vary by about 7mm only throughout the movement. The wheelbase also alters during this movement: longer for slacker angles, shorter for steeper angles.”

So how do you actually adjust the head angle?

Charnaud has designed the Variangle to require no tools so you can adjust it on-the-fly. There are two retaining screws on the side of the headstock that can be loosened and tightened by hand. On top of the headstock is a gold dial that is then turned to adjust the head angle. Once you’ve got the right setting, then it’s a case of tightening down the retaining screws, and you’re done. For safety, one of the clamping bolts actually goes through the side plate and a curved slot in the headstock. This acts as an end stop as well as ensuring that the whole assembly is secure and tight and cannot move unintentionally.

Here’s a video of it in action;

As of right now, the Variangle is still in its early stages of testing and development. Charnaud actually built an earlier version for a wooden full suspension bike (yes, actual wood!) that he took to the Bespoked Handmade Bike Show last year, though that was primarily designed to allow for in-field testing of different head angles. During the testing process, Charnaud was so impressed with the effect of altering the head angle for different situations that he decided to pursue and refine the Variangle concept.

As with the original, the current prototype you see here having been designed, fabricated and tested by Charnaud himself. According to Charnaud, the machined alloy prototype adds 600g to the frame, though he is hoping to develop one out of carbon and epoxy that should halve that weight. He doesn’t wish to produce the item himself, but rather to sell the idea to a larger company. Charnaud firmly believes in the merits of the design, and there are patent applications currently pending in both the US and Europe.

The bike shown in the photos here is also quite the creation that has been handmade by Charnaud. The design might look familiar, and that’s because the silhouette is based around a Devinci Spartan. Charnaud’s bike is very different in execution however, with approximately 130mm of rear travel achieved via a Split Pivot suspension design. Shown up front is a 100m travel fork, though Charnaud is currently testing longer travel forks in there.

Built around the Variangle system, the frame features an alloy subframe with carbon fibre laid over the top. The alloy skeleton forms the basis for all the key mounting points including the suspension pivots, seatpost, bottom bracket, and the Variangle cradle. The rear end of the frame is made from double member alloy plates, with holes drilled through them to reduce some of the weight.

We haven’t had the chance to ride the bike, so we can only speculate from our keyboards. There are certainly some pressing questions around the strength and rigidity of the system, and also how well it will cope with water, mud and Pennine Paste. Charnaud assures us that the design is strong and durable enough, and given the frame is claimed to weigh around 6kg, we’re inclined to believe him!

At the very least, it’s a commendable effort to build something unique. To find out a bit more about the concept and why Charnaud embarked on it in the first place, we dropped him a line to ask some questions.

ST: Was the bike made by yourself?

PC: Indeed so. All the machining, carbon lay-up, milling and turning. There’s a lot of precision milling and turning required. As I said, all the pivot points are in an aluminium subframe inside the frame and through them are brass bushes which are the bearings for the pivots. All this stuff you cannot see which is annoying. The aluminum welding I sub out: there are a couple of welds at the chainstay pivot end.

ST: Where did you make it?

PC: I designed and made this at home in my spare time. I have a Bridgeport J2 milling machine with a precision rotary table for milling all the radiuses (radii?) on the headstock and headstock mountings. Also for the suspension linkage. The turnings and bushes etc are done on a Colchester lathe. Then I have a bandsaw for the rough shaping and cutting out and a large drilling machine. The Bridgeport has digital readouts accurate to a 1000th of a millimetre not that I need that level of accuracy but I do use it to 100th mm accuracy. I am self-taught in machining.

ST: Are you an designer/fabricator/engineer by trade?

PC: My business is selling machine tools, which I obviously have access to. I have always been interested in machines and mechanisms, which is why I love mountain biking among other things. I love the engineering side of things and always when riding I’m thinking how can this be made better. Hence the idea of the variable angle headstock. Sometimes you want slack angles, sometimes steep so why not have both if you can design a system for that? As a rider I just always think how would I improve this ride.

ST: Is this the first bike you’ve built yourself?

PC: No, prior to this I have made several bikes out of wood. But this is the first I have been confident enough to build using carbon fibre.

ST: And lastly; why did you make your own bike?

PC: Good question. As I said it’s not the first and won’t be the last. I can’t explain the feeling of riding your own creation. Especially when you think, maybe wrongly maybe right but you think it anyway that it’s the best bike out there. It always feels that way when you are on something that you have built and you’re caning it down a steep hill and trying to stay upright.

We’d love to hear what you think of Charnaud’s creation, and what your opinion is of the variable head angle concept, so let us know your thoughts in the comments section below!

If you want to see the design in person, Charnaud will be exhibiting at next week’s Bespoked Handmade Bike Show in Bristol, where he will be showing the concept to custom frame builders and the public. And if you want to check out some more of Charnaud’s intriguing prototypes (including the two wooden full suspension bikes shown below!), then check out his website here.

And the point of a 100mm travel bike with a 60 deg head angle is?

(other than being pointless, ie being different for the sake of being different)

it’s just a shame that the BB moves so dramatically as the head angle changes – heightening your BB in the ‘aggresive’ mode would seem counter intuitive to me – I’d be wanting a lower BB to give move stability through corners.

Doesn’t the quoted bit about the frame height varying by 7mm over the range of adjustment also apply to the BB height then?

Great idea for exploring the geometry options.

I’d like to see experiments with a bike with a constant wheel base and differing HAs.

“Now that we’ve moved on from being dicks about wheel size (well, mostly)”…..

We?

The manufacturers have been dicks.

You lot kept your heads down and stayed silent on the subject for years.

“You lot kept your heads down and stayed silent on the subject for years.”

I dunno – we’ve covered all of the developments in wheel sizes, were one of the first people to review 29ers, we’ve interviewed Niner about 27.5in wheels when they came out and commented on myriad wheel and tyre sizes when reviewing bikes. Back in issue 87 we did a ’26 ain’t dead’ bike test where we said that we’d struggled to find three current 26in bikes and that 26 probably was dead. Not sure what more we could have done.

Hi there: The BB height remains the same throughout the travel: the whole thing about the design is that as you alter the angle the following happens: slackening angle:

wheelbase lengthens,

centre of gravity moves further back,

bar moves back,

ride height stays the same,

BB height stays the same,

thanks for the interest by the way. please ask your favorite bike manufacturer to build one. You would not be disappointed : thats a promise !

By the way (cx_monkey) The system could be designed with a lowering BB if you required that. Its just a question of where the “virtual pivot point” in front of the bike is located. The virtual pivot point is the centre of the circle of rotation of the headstock. At the moment it is 225mm in front and level with the bottom of the headtube. But to make it so that this changes you would simply raise where that point was . My whole design effort has been to keep the height the same but at virtually every other position for the pivot point it does have the effect of altering the ride height and BB height.

“Not sure what more we could have done”.

Given an opinion?

Acknowledged that there was a downside?

Asked a few awkward questions?

Basically, we got “Things are changing, get used to it”.

Yes, we did get your article in the mag, a couple of years after the introduction of 650b, but too little, too late.

Basically, I feel you didn’t represent or properly acknowledge the implications for a significant proportion of your readership.

Rusty,

Surely the magazines remit is not to attempt to crusade against or for a particular wheel size?

Anyway, back to the topic, I wish the designer of the Variangle all the best with the future development and uptake of the design. Pretty ingenious and way beyond anything I could think up!

Thanks for explaining that @pjcharnaud – makes sense when I sit and think about it a bit more carefully!

Poopscoop, I agree, maybe my expectations are a little too high.

I trust the opinion of the STW staff for various reasons and find their opinions most often reflect those of those I ride with.

Lovely bike btw and an interesting read too.