Luke Bradley attempts to discover if you can Interrail through Switzerland like a student, only with a mountain bike and high-zoot locations like Davos in your sights.

Words and photos: Luke Ellis Bradley

Hey, this feature looks even better when viewed via Pocketmags; you get the full graphic designed layout on your device FOR FREE! It’s not quite as beautiful as the paper magazine but it’s better than a basic webpage.

Trains are having a moment right now. Francis Bourgeois has taken trainspotting to the TikTok generation, the railways are being renationalised and the model railway in my attic is coming along brilliantly. The passenger railway turns 200 years old in 2025 – the Stockton and Darlington Railway in the North East of England started hauling patrons in 1825. Originally, a goods wagon with a roof was used to store trunks and cases, and in the following 150 years, passengers were able to travel with their horses, cattle and even cars. Why, then, is travelling with a bike now so difficult? The loss of luggage and guard’s compartments to maximise seat space since the 1980s has made going on holiday by bike on the train a pain, and I wondered if there was a better way. With that in mind, I head to Switzerland, hardtail in hand, to see how this meticulous country handles bikes as baggage.

The first faff

The first train I catch, from Geneva to Brig, departs on time and has a relaxed conductor who is patient while I faff with my Interrail ticket. Once the reserve of the young, Interrail passes are now available to anyone of any age. Mine cost about £150 with unlimited travel in Switzerland for a few days, and because my bike is in a bag, no extra charges or reservations are needed. The train fills up with cyclists as the trip progresses. There are a couple on hybrids, a retiree with an electric gravel bike and mountain bikers. Different groups chatter to one another about routes and gear – including some genial discussion about how flagrant the pensioner’s exceedance of his frame’s maximum tyre clearance is. You couldn’t fit a fag paper between the tyre and the frame.

One of the good (and bad) things about travelling by train are the people you meet. SBB (Swiss railways) staff are all friendly and understanding, and I meet several Brits doing rail tours of Switzerland. One highlight is a group of Americans who are paragliding across the Alps and catching the train towards the next chairlift. On the other hand, the crowd from Birmingham playing a game of ‘Who did that fart?’ in a carriage vestibule was most certainly a lowlight, as was the stressful moment when the police on the train at the Italian border briefly thought I was with the woman sitting next to me who was carrying a jar full of weed in her handbag. Generally, however, between the views and the company, I don’t even have time to read my book.

Stone Age cycling? Hardly

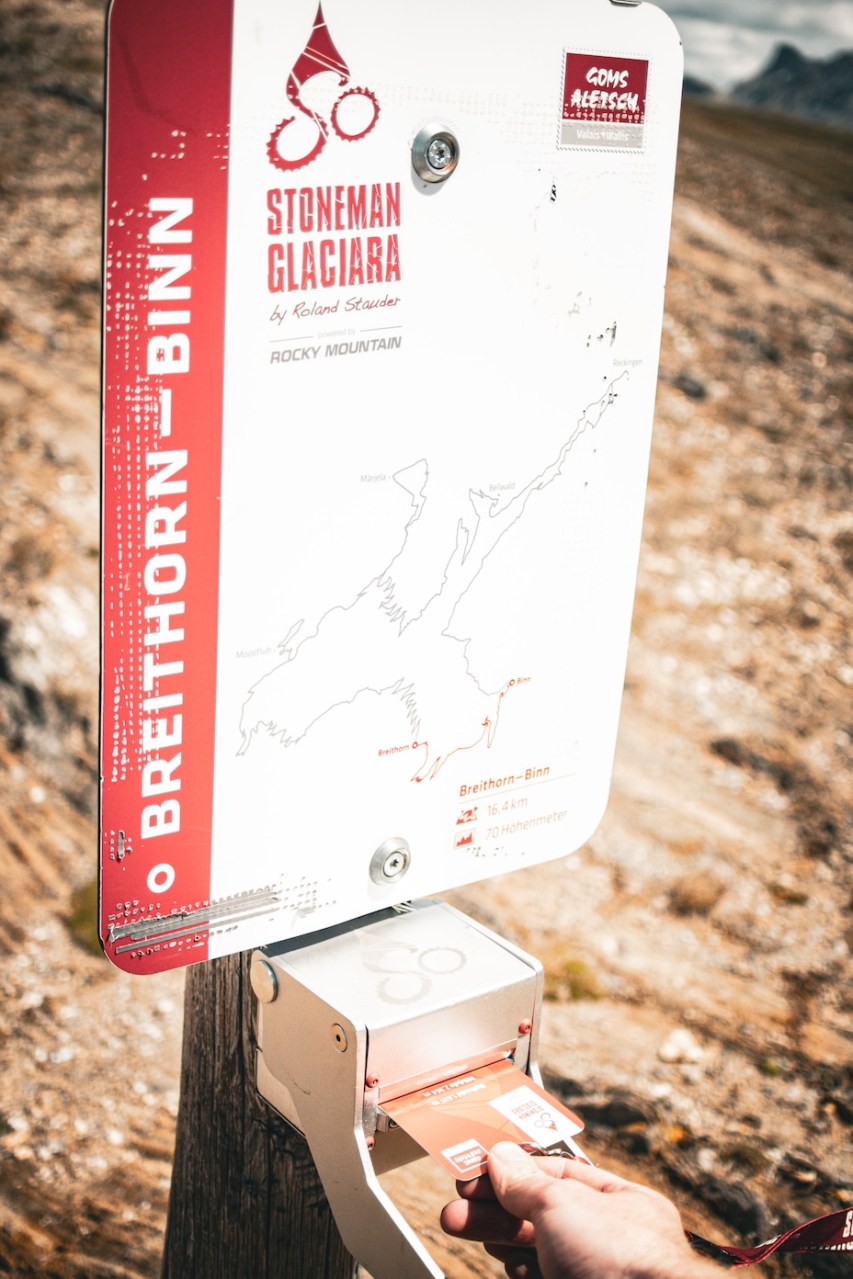

I’m heading to Brig to ride a route called the Stoneman Glaciara. This 121km circuit is the cross-country side of life in Valais. The MTB World Championships are about to start and given that so many Brits head to the Alps with big full suspension bikes and dreams of chairlifted downhill laps, I wanted to see if the long-distance stuff was enjoyable too. The Glaciara is one of six Stoneman routes – there are others in Italy, Germany, Belgium, Czechia and Austria – they are clear, well-signposted routes with checkpoints where you stamp a card.

This one goes through the Aletsch Arena. The Arena is named after the Alps’ biggest glacier, stretching 23km from the Eiger in the north to Bettmerhorn, and the Stoneman route in the south. The area has several castles built by Brits and as a result, Brig has hotels and pubs with names like Angleterre and Big Ben. The trains bear little resemblance to UK ones, though – three carriages with spaces for 24 bikes running on narrow gauge tracks high into the mountains.

I wheel my bike onto the little train and head to my start point in Mörel. From here, the route climbs 1,500m in one go to the Breithorn. It takes me hours, and in the valley bottom below, the sound of the trains beats out a half-hourly rhythm. Three trains-worth of time pass, and I catch up with Ken and Geraldine from Ken’s bike shop in nearby Visp. They’re riding at roughly my pace, although these heroes are riding the whole thing in one day rather than two. They guide me down the Breithorn descent – which is, unfortunately, all gravel road. They’re grateful – they are, after all, already about 4,000m of climbing into their day and a bit cross-eyed. While I’d hoped for more engaging terrain, it is stunningly beautiful and we pat friendly cows, wave at marmots, cruise through floral Alpine meadows and soak in the scenery. At the bottom, the Stoneman flows gently along the valley bottom before doubling back on itself down the opposite side of the valley to Fiesch and my hotel (which, by the way, had a bloody ‘beer sommelier’ – a dangerous thing with another few thousand metres to climb first thing in the morning).

Wrong side of the mountain tracks

The next morning, I meet Gian-Luca from another local bike shop, Bike Aletsch in Mörel. Once up in the ski resort of Fiescheralp, we pedal through a tunnel built to carry water to the surprisingly arid villages on the northern slopes of the valley and, for the first time, leave the railway out of sight and hearing range. On the other side, Gian-Luca suggests we ride a technical-looking trail to get a peek at the glacier before rejoining the Stoneman. It seems like a typical Scottish natural descent and I assure him I can handle it. Which I could, until after the end of the technical section when I clip a rock at the side of the trail and smash my face down onto a boulder. My nose is split open and my lips are bleeding. The boulder is spattered with blood, as if I’d been sacrificed to the Alpine gods. Gian-Luca swears a bit.

This is the Alps, so despite there not being a road or house for kilometres around, there’s a restaurant for hikers. They let me clean myself up and we carry on our way, still having not seen the glacier. Immediately, the trails are totally different to yesterday – slightly technical, rocky, twisting singletrack, clinging to the mountainside. We’re both on short travel bikes and they’re not far off their limit, but anything bigger would be overkill.

The day carries on in this vein – while I’d been sceptical after the first day, everything here makes up for it. All the descents are the right side of fun – not boring, but not full-on tech. I’m able to soak in the magnificence of the Aletsch glacier when we eventually see it at the Moosfluh viewpoint, and from there we have nothing but descent to look forward to. After some lightly modified natural singletrack, tweaked just enough to be perfect for bikes, we’re briefly on a brand-new flow trail with perfect tabletops. The finale is along what used to be the road up to the mountain tops when only shepherds on horses went up there – rocky, twisting and with little jumps built by Gian-Luca and his friends when they were teenagers.

Ice creams, pharmacies and express trains

After an ice cream to soothe my swollen lips, I start my train journey east towards Val Müstair and I come up against a problem that seems inconceivable. A Swiss train is running late. Not very late, about seven minutes, but the connections recommended by SBB are all tight – they, too, assume that all their trains will run on time. As a result, I miss the first connection by two minutes and that adds an hour to my journey. I’ll arrive after hotel check-in closes, and lord knows if I’ll be able to find somewhere to stay. At least this gives me time to head to the pharmacy in the station and get hold of some bandages and ointment to soothe my wounds.

To make up for it, the intercity train is enormously comfortable – second-class seats are akin to East Coast First Class in the UK, and there’s bike space in four of the eight carriages, so my bike bag slots right in. In Basel, I switch onto a French TGV. This wasn’t the plan, but because of the earlier delay this is the last train that will get me where I need to be in time to ride tomorrow. After rushing across six platforms, I find that it doesn’t take bikes, but I confidently wheel my bike bag past a group of conductors on the platform and step into a carriage – not one eyelid is batted.

I indulge in a meal in the bar car. The man behind the counter is exceptionally nice and concerned that I look like I’ve been in a fight. The croque monsieur I order to keep me going through the night is not quite the “Delicieux Voyage” the posters promise, but it tastes like actual food, and he makes it in front of me – very different from the service at home. It’s also on the upper deck with seats facing outwards, a real luxury with great views of the surrounding countryside and the Lindt factory. Once I arrive in Zurich, the connection is tight again, but this time everything works flawlessly – two more connections and five relaxing hours later, I am on the last train to my hotel for the night in Susch.

Oh susch!

I see the word Susch on a locomotive shed and collect my bike, ready to get off, but the train just flies through the station without stopping. My absolute lack of German means I don’t understand the ‘request stop’ announcement (French and Italian are official languages but all train announcements seem to be in German). I arrive one stop down the line, 20km away, at about midnight, in the pouring rain and after the last train back up the line has gone, in a town with no open hotels. It’s Swiss National Day – there are a few drunks milling about post-party, but none of them can help. Staring down the barrel of a night on a metal bench in the rain, I eventually find some teenagers waiting for their dad, who is, thank god, the chef at a hotel and can sort me a room. A slip for rail travel, then, but in reality, this is my own fault for not understanding the language.

Back on track(s)

After a short train ride the next morning, then a trip on a bus (which has a trailer for taking bikes), I am greeted in Val Müstair by Nicci, who teaches at Ride La Val, the local mountain bike school. Nicci clearly absolutely loves riding her bike and with the trails she shows me, I can see why. Our first ride stays low in the valley to dodge the worst of the rain. The trails flow through woodland, flowers all around us and it’s joyous. We reach Lü, one of the highest villages in Europe, nestled at almost 2,000m, and after being introduced to Romansh, the local language, over a brew in the delightful Pension Hirschen, it’s downhill all the way back on superb loamy singletrack.

The next morning, Nicci takes me up into the mountains. We could take a public bus to the border with Italy, but then it’s hikeabike for 500m. The ride takes you through a kind of Narnia – barren rock covered in ice and fresh snow which, over the course of the ride, drops past sparkling blue lakes, tumbling streams and lush, verdant forests and though with marmots instead of Mr Tumnus. The whole of Val Müstair feels like a more natural Switzerland – trails built for a purpose, not for visitors, and much quieter and more idyllic. The trail itself is superlative – technical and rocky at the top, with the odd bit of exposure, before dropping steeply via a series of endo-tastic switchbacks and then relaxing on flowing singletrack on the forest floor.

The following morning, I get back on the bus (the driver almost gleefully hopping out to help put my bike bag in the storage compartment), and enjoy a seamless train ride up to Davos, clinging to a gorge and crossing the imposing UNESCO-protected Landwasser viaduct. You’ll know Davos for the annual World Economic Forum meetings, but it’s also a popular resort with a bike park and trail network. It’s a favourite skiing spot of the British royal family, and my hotel has a signed photo of the Duchess of York behind the desk. Despite being a hub of activity for the wealthy, it’s actually pretty cheap to stay here in summer when the town seems to go into tick-over mode. I get free train travel and a lift pass with my hotel, which was Premier Inn rather than Ritz price, and it’s only eating out in the evening that really strains the wallet. It’s very different to the Valais and Val Müstair areas – it seems to play less on Swiss charm, and rather than chalets, the town centre is populated by luxurious modern hotels and stores.

I’m pointed in the direction of the Alps Epic Trail by the owner of my hotel, who’s a keen rider. Compared to the bike park, which has a small selection of flowy downhill tracks, this is very much in the ‘nice day out’ category. The trails are all hiking paths, and largely smooth, twisting singletrack following the contour lines along the valley. Even in the pouring rain that’s moved in, it’s delightful. For the last half, it follows the railway line through a canyon back to Filisur. I hop on a train back to the hotel, looking forward to exploring further but temperatures plummet overnight and the trails are covered with snow and closed for two days. The trains, however, keep running.

I can see George Clooney’s house from here!

To finish, I head to another opulent spot – Lake Como. Easily accessed by train from Switzerland, this lengthy journey is also without hitch on the Swiss side – there’s space for so many bikes that I effortlessly fit mine in on every train, and the comfy seats and magnificent lakeside views mean the five hours fly by. The Italian trains worry me – in a country where Mussolini famously made them run on time, my previous experience with them was chaotic, with every train delayed and without any noticeboards or announcements to help but I thought putting them in a head-to-head with the Swiss railway would give a full view of modern bike-accessible train travel in Europe.

Sure enough, even before we cross the border, things are going wrong. The aforementioned drug bust delays us ten minutes as the woman with the illicit ounce is taken off the train by border guards and a lot of arguing and crying ensues before she’s let back on. I had hoped to have a final treat in Como by taking the funicular to the top of the hill and riding down, but the queues are so long and the service so slow it’s quicker to ride in the heat.

The ride is good, but Como doesn’t have that Alpine feel, being in the foothills, and the trails I ride are more like technical trails to keep local riders amused rather than something deserving of a visit from abroad. I arrive back at the station just in time, but the connecting train is ten minutes late so I miss another connection and arrive two hours behind time. Almost all the info screens at the stations are dead, so I don’t know where to go for my next train. The trains are as new as the Swiss ones but scruffier, and the toilets were frankly terrifying. Mussolini will be spinning in his grave. Although, compared to the UK, no one ever has a problem with my unreserved bike.

For comparison, when my flight lands back in the UK, I take the train home. The Trans-Pennine Express guard pounces on me when she sees my bike bag, making sure I have a reservation – the first time I’ve been asked this trip. The cycle space is pointlessly tiny – if my bike were assembled, it simply wouldn’t fit. The other trains in Newcastle station date as far back as the 1980s, much older than the European trains. The train is also too short for the number of passengers – dozens are standing, while everyone in Switzerland and Italy had a seat, and space around them.

Punch tickets, not car horns

It turns out that, yes, you can visit some of the best riding spots in a country by train, although it depends on which country – I’d not do this in Italy again. It takes some determination, and it really helps if you at least learn some of the basic words required for train travel in the local language so you’re able to take pleasure in the scenery and see the journey as an opportunity to soak in the country around you, rather than as a barrier to your riding. You also have to budget for contingency – if you’re in your own car, you can change plans on the fly, but by rail you need to make sure you have a buffer of another train after the one you intend to catch, just in case you miss it. You’re tied to a schedule, which isn’t always convenient. Having your bike in a bag often makes it easier to get on, as you can blag that it’s baggage if you don’t have a reservation. One of the big worries for people seems to be cost. My £150 pass cost less than a hire car big enough to carry a bike for the same period, even before taking fuel into account, and it was so much more restful than driving myself. I’d definitely do it again.

This made me want to watch VAST again. Red travellliiiinnnnn socks

Combining MTB and trains in Switzerland is fantastic. Can get train up one valley and ride to a station in next valley. Frequency and extent of network is quite amazing. Get the SBB app for station maps for transfers and platform updates etc. Normally bike in bag is free, otherwise need to buy bike pass for 15 CHF per day

Ive gone all Kurtz after reading this

“SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS FIND SOMEONE ELSE FORGET IT! I’M NEVER COMING HOME”

Looks incredible… and so does the bike! What frame is that?

@2orangey4crows – it’s a Sour Crumble from Germany and it was far, far more capable than a little bike with SID forks on it deserved to be down the big stuff.