Tom Johnstone rides across Iceland’s interior and learns that making your dreams come true isn’t always easy.

Words & Photography Tom Johnstone

This was an adventure I’d dreamed about for years – 15 to be exact. Every winter since I was 18 I’ve said ‘next summer I’m going to ride my bike across Iceland’. Every year there was a reason why ‘this summer’ couldn’t be the one. This year there was no reason not to go, so the flights were booked, sponsorship deals secured, and a rough plan hatched. I knew this trip would be tough, but it wasn’t the long days in, or worse, out of the saddle, the washboard gravel, or the potential for bad weather that worried me. This time I knew I would either be my own worst enemy or my own saviour when things got tough.

Winds of change.

The last few years have put many difficulties in my path. While I’ve been growing my mountain bike guiding business and freelancing, life has been throwing curve balls of monstrous proportions at me. In 2010 I met my wife to be, in 2012 we were married, in 2013 she was diagnosed with cancer, and in 2014 we were told it was terminal. September 2016 saw Catherine’s prognosis come true and she died with her mum and me holding her hands. She was 40.

I went from running a business so I could help keep a roof over our heads to having no one to fend for but myself and, suddenly, the ‘freedom’ to do what I wanted. Life seemed fragile, too short and far too unknown. I decided that 15 years of saying ‘next year’ needed to end, and so I found myself alone in my tent on the south coast of Iceland, listening to a howling wind.

Seeds of doubt.

I loaded up and with a glance over my shoulder at the south coast of Iceland and the barren sea beyond I headed north, my general direction for the following week. The ride to the road was brutal, the ride along the road to the waterfall at Skogar was terrifying as side gusts blew me clean across the road into oncoming trucks and bewildered tourists in campervans. I made it unscathed to the turnoff, glad I wouldn’t have to deal with traffic-riddled tarmac again until rejoining Route 1 at the top of the island.

The first climb is roughly equal to riding up Snowdon, a ride I guide ten or more times a year, so even given the extra weight of a week’s worth of food and equipment I was confident in my baseline fitness. This confidence evaporated rapidly over the first hour; two hours in I was lying in the middle of the track cursing my lack of fitness. After a few hours I met four Canadian riders heading down the trail in the opposite direction who stopped for a chat, mostly from curiosity. They offered me a ride around from Skogar into the next valley so I could skip this first day; the one they said is definitely unrideable on a fully laden bikepacking rig. I was torn – there was no way I wanted to give up already, but these guys really did seem to know what they were talking about; they were real bikers who’d just done my ride the opposite way around.

Part of me wanted that sanctuary, that guarantee that I could make it to the first campsite. The other part of me knew that if I turned around then, I’d head home, give up at the first hurdle, and probably spend the rest of the month hiding beneath my duvet, unable to face the world of ‘real’ mountain bikers.

I pushed on, crossing snowfields, lava flows and barren dusty stretches of trail with indistinct paths, just the occasional marker post in the distance to lead me on. The whole day was excruciating. I found myself haunted by a doubting voice, one that repeatedly told me for hours on end ‘you’ve bitten off more than you can chew here’, ‘you’re not fit enough’, and ‘you’re not a real bikepacking adventurer, you should’ve stayed at home’. Somehow my legs disconnected from this voice and kept pushing me skyward.

As I pushed along the crux move, a ridgeline with a 400ft drop off each side that even hikers were looking rattled by, I knew that I was now committed. Unable to retreat, some of those nagging voices quietened – even if I wanted to give up I couldn’t, there was no going back to the start. That first night’s campsite was a joyous achievement. After 13 hours of riding and pushing and self-doubting, I had succeeded and completed day one as planned. I don’t remember my legs or lungs aching, but they must have done. What I do remember is the immense mental respite I got that evening as self-doubt quietened in the face of success, but the next morning gave it a new dawn upon which to cast uncertainties.

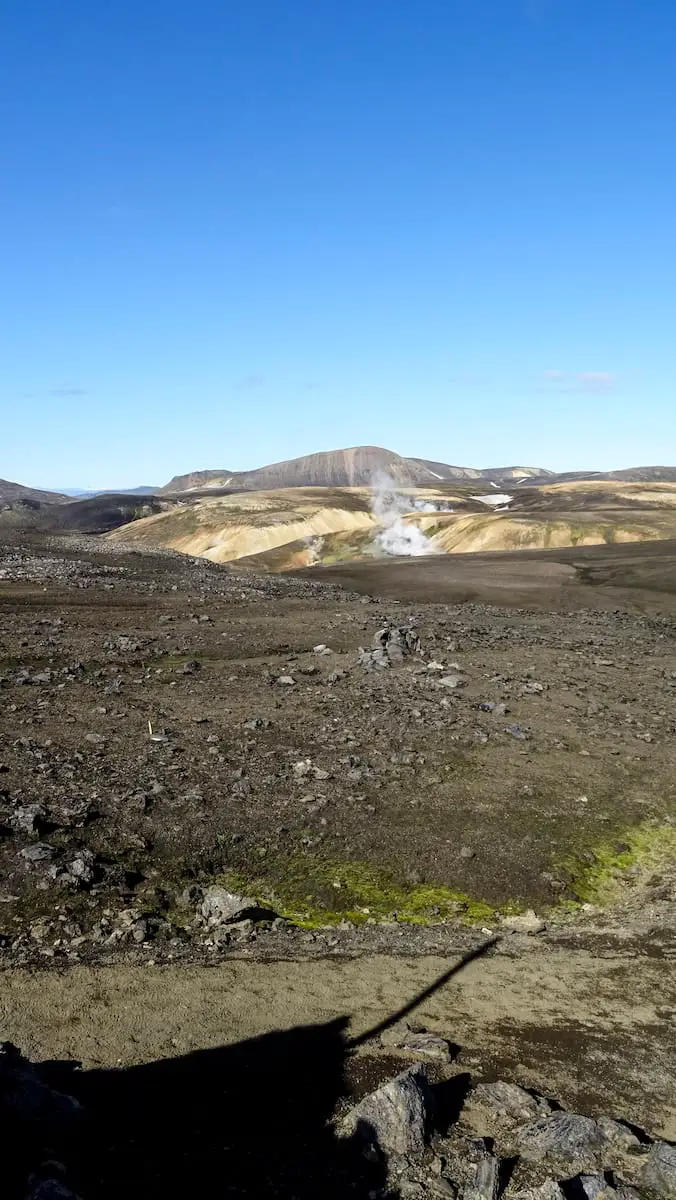

The next two days to Landmanalugar saw me pass through some of the most unique and incredible scenery on earth, while inside I was gripped by an emotional roller coaster of epic proportions. I bounced from being overjoyed by the awesome landscape to being plagued by doubt. Creepingly slow progress made me question the wisdom of my itinerary (despite knowing very well that this entire trip was achievable in the time frame I’d set myself). I stopped often to talk to hikers heading the other way to distract myself from the little black dog of anxiety who’d invited himself along on my trip. Those I spoke to marvelled at my ability, my strength and tenacity for taking on a solo trip like this, on a route they were finding tough going on foot. I basked in this while it lasted and felt my spirits lift, but as soon as they turned and continued their journey south, my little black dog came straight back out, snapping at my heels. While crossing fields of obsidian, I spent the whole time flitting fearfully between envisaging the damage it could do to my tyres, then to the damage it could do to my knees. But when I finally started to descend toward Landmannalaugar, the scenery got the better of my self-doubt and I was, once more, utterly captivated by the sights spreading out before me.

Landmannalaugar is indescribable and the happiness it brought me to arrive here, on schedule, having suffered no real setbacks or delays, was immense. As I soaked in the hot pools, I felt my anxiety relaxing and for the first time thought ‘I might actually do this’. I stood to change clothes by my bike on the boardwalk, careful to not overspill onto the fragile grasses and flowers bordering either side, but a member of staff concentrated scornful glares in my direction and spoiled the moment. Unable to grasp what I’d done, because I was keeping myself out of other people’s way, staying off the grass, and being significantly better behaved than many of my fellow bathers, I continued to change and tried to shake off the dark cloud she was casting in my direction. As I left she confronted me with a tirade of scornful remarks about how disrespectful I was having a bike here, that I clearly didn’t love nature and how I wasn’t welcome. I was told to go home and find nature to enjoy somewhere else. Dumbfounded, I couldn’t comprehend what I’d done. I was the only cyclist in the area, but I’d been careful not to damage the fragile ecosystem, stayed out of the way of other visitors and was polite toward the staff I’d encountered – clearly this was not enough. Knowing I was unwelcome, I got back on my bike and rode away, giving up the relaxed and sociable night in the campsite I’d been looking forward to before heading into the empty heart of the island.

Coming undone.

On leaving Landmannalaugar I thought I was experiencing the fabled washboard gravel roads – little did I know I was on the infant school version and in the days to come I’d take on the university level washboard of the interior. A few kilometres down the road one of my fork cages came loose. It was a simple fix and I was soon riding again. A few kilometres later and my front wheel lost tension, the rim swaying terrifyingly from side to side on spokes that held no tension. Again the fix didn’t take long, but these mechanicals on top of the situation at the hot pools meant my doubting mind returned. I struggled to find a suitable spot to camp in that night and ended up on a patch of gravel just off the shoulder of the F26.

The following days I journeyed through a landscape so sparse and wide open that I could ride for an hour and barely notice any change. This started to take its toll on my senses and my body; my mind started its own monologue that flitted between cathartic and debilitating.

Unhappy anniversary.

This was the only window in my summer that allowed for the trip, so I was cycling through the interior one year after Catherine’s last month with us. Halfway across Iceland was the anniversary of the day I’d realised I could no longer care for her properly at home. I was so against her going into the hospice; I’d wrongly built up an image in my mind that the hospice was where old people went to die and, while deep down I knew Catherine had only weeks to live, she wasn’t old and I felt my duty was to care for her at home. Of course I was wrong and the hospice was the best place for her to be during her last weeks. The staff at St David’s Hospice proved to be professional, compassionate and caring in a way I never realised was possible and they looked after her and me so wonderfully I’ll forever be indebted to them. They made her final days comfortable and free from pain. They allowed her to die with her mum and me holding her hands.

Having all these memories and emotions to contend with drove me on. I craved human interaction and distraction and I just couldn’t face being alone in the brutal interior any longer. The lack of stimulation and the unceasing battering from the inhospitable gravel road beneath me really took its toll.

Sitting here now I struggle to separate out the three days I spent alone in there. I remember meeting two cyclists; one who just rode straight past me like I didn’t exist, crushing my hopes of sharing a few words with another human that morning. Another who was as eager as me for some human contact and who is still in touch now we’ve both finished our trips and moved on to adventures new. There was the hut warden who fed me hot chocolate and allowed me to sit by the fire to warm myself after a 120km day. I arrived at her door barely able to string a sentence together, having utterly depleted myself in the final hours of the day getting to the hut in the hope of shelter from the wind overnight. Toward the end of the crossing I found a bicycle tyre with a split in it, discarded by the side of the road. Incredulous that someone would carry a spare all the way out here and then see fit to dump their knackered one in this wilderness, I strapped it to the front of my bike and hauled it out for them. That tyre is now a belt I wear with pride and that cyclist is a dick who owes me a pizza (I spent a full 36 hours dreaming about pizza while staring at that tyre on my bars).

Eternally grapeful.

Summiting the final rise, I looked down toward the coast and the start of my glorious descent, only to face a headwind so strong it stopped me dead in my tracks mid-descent. Utterly broken I lay down behind the only shelter I could find from the wind, a small boulder only big enough to shelter my head and shoulders, and did all I could to ignore the sand and dust whipping around me and stinging my tender calves. Eventually I accepted my fate and got back on my bike to pedal down every inch of that descent, fighting the headwind the whole way. Clearing the final crest and realising that no matter what the weather did now I would make it to the north coast and complete my trip, I found my eyes overflowing and tears streaming down my face. Tears of relief at knowing this trip would be completed, but more than that, tears of all the emotions I’d battled as I crossed the interior.

On reaching the tarmac of Route 1, I crouched to hug its joyous, solid, smooth firmness, delirious with the knowledge the washboard was over. Less than a kilometre down the road I pulled into the Godafoss waterfall viewing area. Finding nowhere to sit, I collapsed on the floor next to my bike. I had no idea how dirty, dusty, and exhausted I looked, but a minute later an American woman approached me with a bag of grapes and an apple. I had no words at all; I stared dumbfounded as she handed me fresh fruit. My dehydrated meals on this trip were incredible, the best I’ve ever had, but fresh fruit was something else. Between stuffing grapes into my mouth, I thanked her over and over, slowly regaining the energy to recount some of my journey to her. Overhearing this, an Italian couple thrust a peanut butter sandwich into my hand. These people will never have any idea how incredible their simple generosity felt to me.

From there to the top of the island it’s tarmac all the way and before the sun crept down toward the horizon that night I was pitched up on real grass, with soil beneath my sleeping pad instead of gravel and sand. I ventured into the local swimming baths, showering twice before getting in the hot pools, and then once more afterwards just for the luxury of it.

The meaning of bikes.

The ride across Iceland was one of the hardest I have ever done. I learnt things about my bike, my set-up and my clothing, but most of all I learnt a lot about challenging myself. I’ve not yet done a ride that has ‘broken’ me, forcing me to stop or drop out, and I had thought I needed to keep going until I found such a ride – my ‘ceiling’. Iceland made me understand that no ride will ever be as hard as sitting by Catherine’s bedside and watching her life slowly ebb away. Nothing I will ever do will be as hard as the moment I had to let go of her hand and walk out of that hospice knowing she was gone and I’d never see her again.

It’s taken me six months to process my feelings about this journey and come to terms with it enough to sit down and write about it. Trying to work out what I’d learnt from the trip was hard, because thinking about the mental suffering on that journey reopened wounds that are still trying to heal. I have come to understand that one reason we push ourselves and take on great physical endurance events is to test ourselves mentally. I’ve been challenged far harder over the last few years than any bike ride could ever test me, which has freed me from feeling the need to prove myself on the bike. Since returning from Iceland I’ve ridden more trials, more downhill and more street, just for fun. I still love guiding bikepacking trips, but have realised that for me biking is about enjoyment and riding with great people. Some people will always feel the need to test themselves on the bike, but, for me, riding is now about playtime and having fun.

The topic ‘Singletrack Magazine Issue 118: Internal Struggle’ is closed to new replies.