Who makes all of those pieces that make a bike more than a pile of tubes? We meet the people who make the bits for the people who make the bikes.

Words by Hannah and Fahzure Freeride, Pictures by Hannah

Many of us never give much thought to the idea of owning a handmade bike, probably dismissing the idea as too expensive. The reality is that a handmade bike is often cheaper than we might think and unlike most off-the-shelf experiences, a handmade bike purchase will almost certainly involve more insight, customisation and support. Let’s say you do think about handmade bikes from time to time. Maybe you go to a show like Bespoked and admire some, talk to the builders. You look at the neat welds, the artful bends in the tubes, the way the angles balance out just so. Maybe you’re impressed by a neat, practical little feature or a functionless flourish of beauty. You probably give the paint job a second (or third) glance.

But have you ever stopped to look at the head tube, or the bottom bracket shell, or the cable stops? Did you ever wonder where the brake mounts were made? Unless you’ve ever made a frame yourself, probably not. If you’ve ever got as far as wondering where you might buy a bottom bracket shell, you’ve almost certainly heard of Paragon Machine Works.

Factory farming

Based in Richmond, California, an industrial city with a very diverse population that’s just across a bridge from San Francisco, Paragon Machine Works is the framebuilder’s builder. Approaching the small industrial unit, we turn through streets that appear solidly working class. Many gardens (or yards, as they’re called here) contain a car that doesn’t look like it’s moved in a while, plus another that doesn’t look like it’ll be moving for much longer. But it doesn’t feel deprived or dangerous in the way that other neighbourhoods in California can. There’s no threat behind the broken windows and peeling paint, just a lack of time and money to fix things between all the other demands of life.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

Turning into what ought to be the factory yard, we find ourselves in a garden. A huge pergola construction festooned with wisteria, jasmine and trumpet flowers casts shade over carefully planted flower beds that are interspersed with ceramic sculptures and containers. The sweet scent of the climbing plants mingles with the roses and herbs, so that the usual factory smell of hot metal and cutting oil is nearly absent.

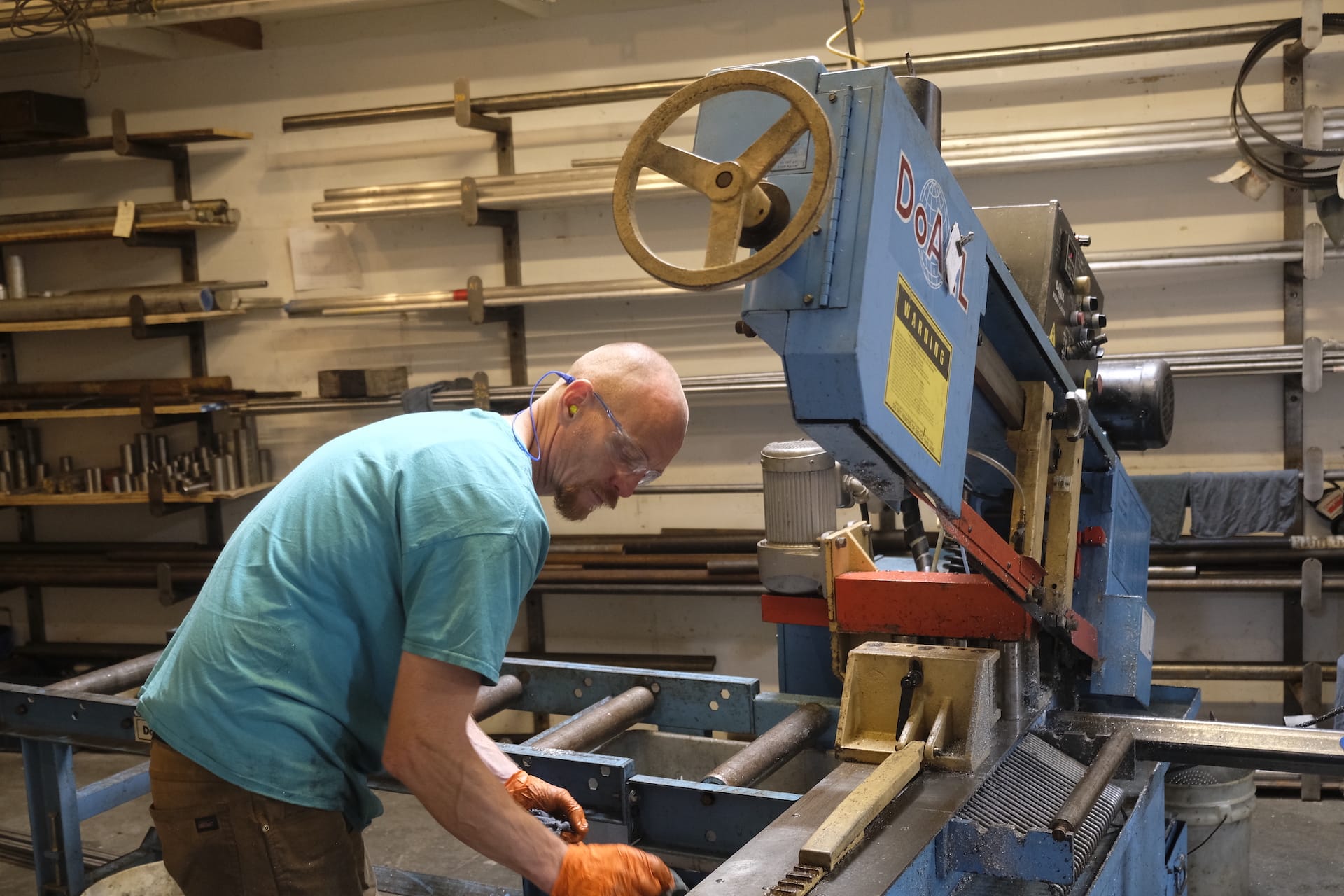

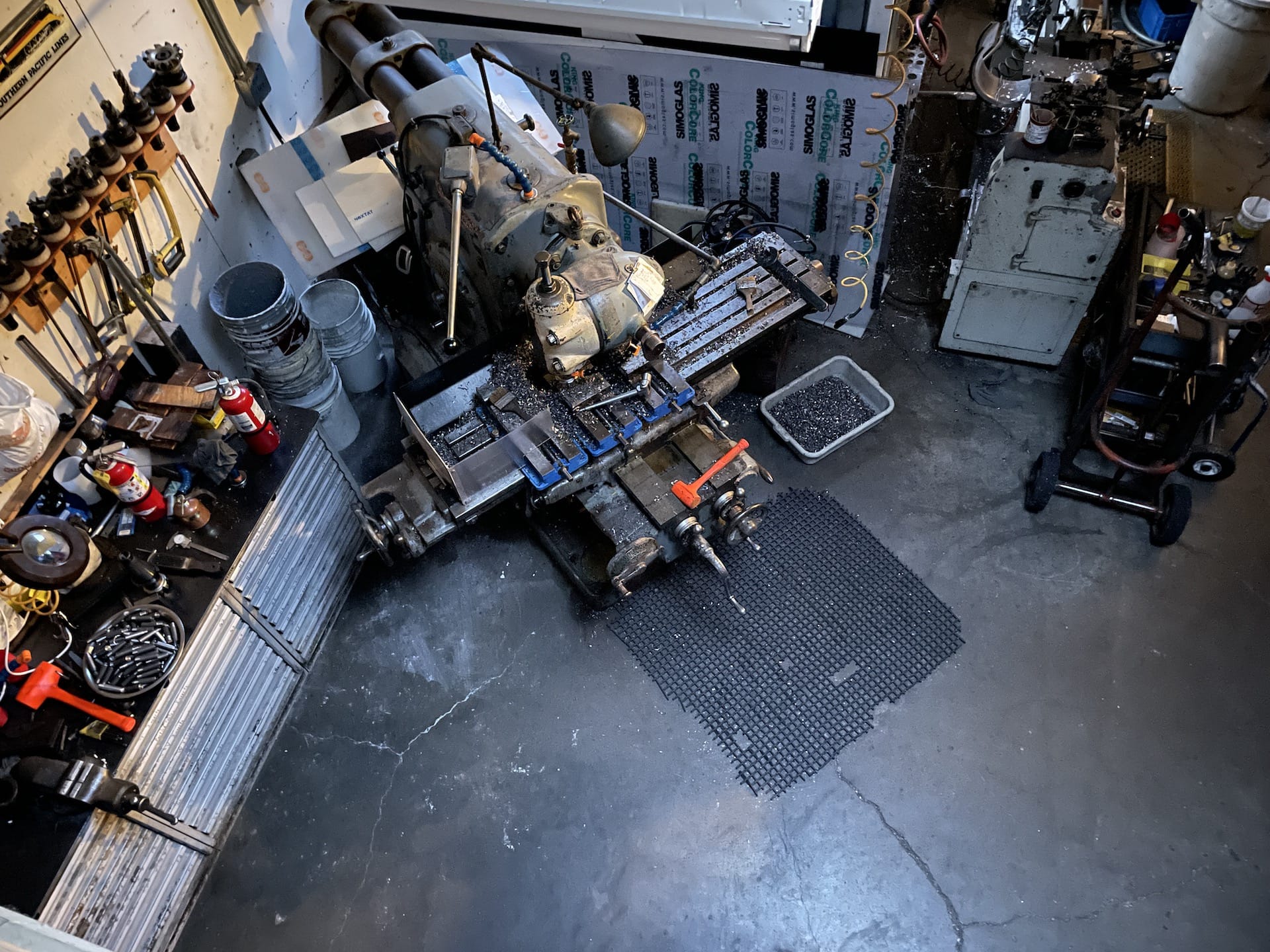

The pergola sits between three sides of a building, where large windows give sight through to engineering machines. There are old hulks of metal turning machines painted in those shades of blue and green that must have been bulk ordered by every lathe and machine maker in the world in about 1920. Between the complex shapes of the older machines sit the off-white boxes of modern CNC machines. Bikes parked on a rack – interesting ones that show telltale signs of being owned by enthusiasts – draw us in towards blue-grey wooden doors with more large windows; the whole external appearance makes us feel more like we should be heading into an art studio than an engineering works.

Indeed, the home of Paragon Machine Works has art of sorts in its history. The building was designed by founder Mark Norstad’s father, who was both an architect and a ceramist. Hence the interesting collection of American arts and crafts pottery in the garden. Mark and his brothers helped build the U-shaped two-storey unit in 1981 before starting Paragon Machine Works in 1983 as a small operation in his parent’s basement across the water in Marin County. Eventually Mark moved the business into this unit, configuring it with material storage, shop, finishing, recycling, kitchen, inventory, and even an apartment space. The factory is a pleasant place to stay. Mark has a tenant in another apartment who’s growing a fine crop of vegetables in one corner of the garden, and has lived in the place for ten years. Either it’s a nice place to live, or Mark is a good landlord. Maybe it’s both.

Coffee and donuts

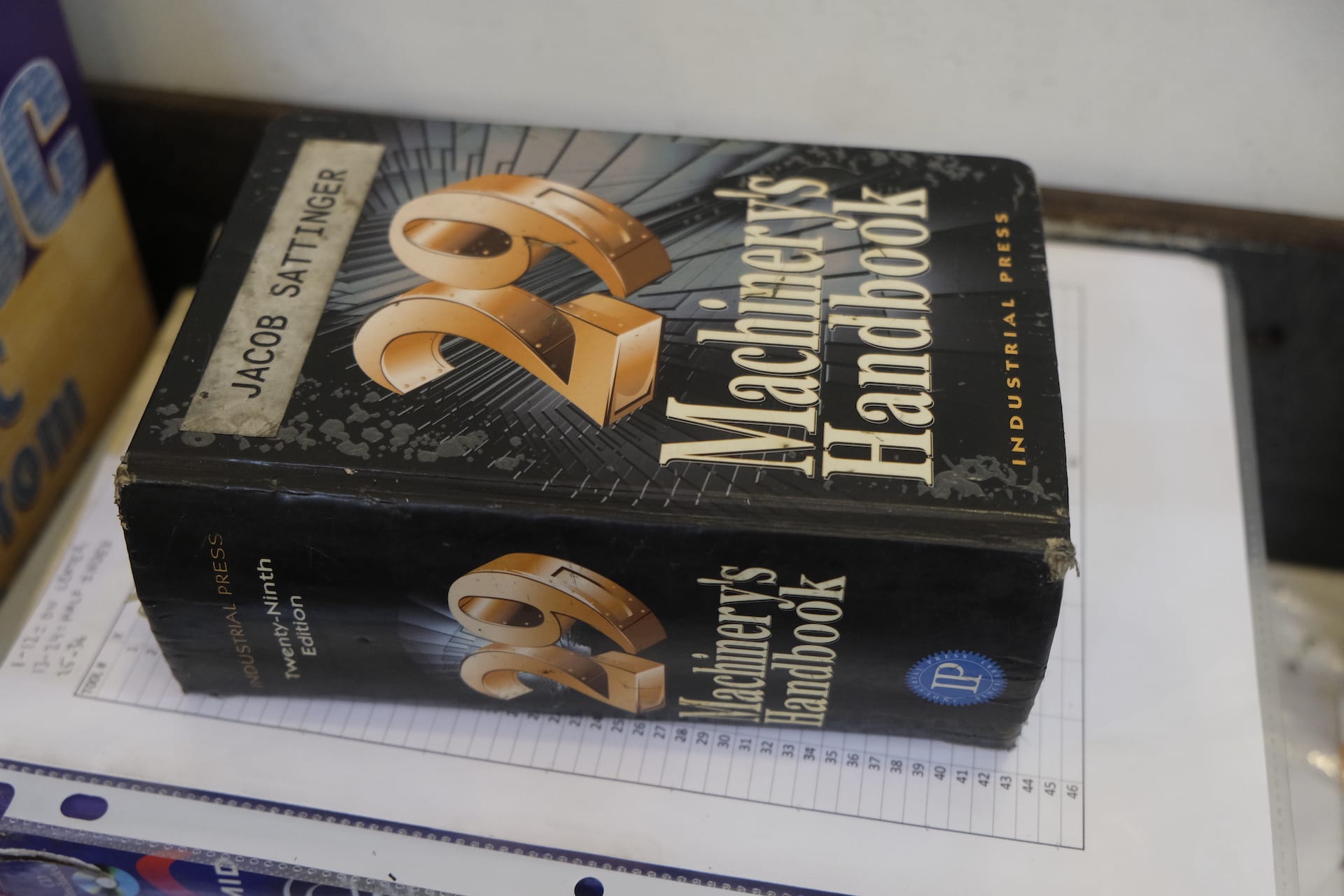

As we finally drag ourselves past the ‘Paul Components’ equipped bike outside and the pirate bones logo on the door, we’re invited to grab coffee and donuts and go exploring, while the staff finish up their team meeting. With the machines largely still, the factory is relatively quiet though this doesn’t last long. As the team meeting ends and the staff turn on their machines, they also fit earplugs against the background roar as each gets underway with making the day’s product.

Paragon Machine Works makes predominantly bike building components from titanium, aluminium, steel, and stainless steel. You can get headtubes up to 280mm long – often ridden by NBA basketballers. Front dropouts – for some reason most of their 15mm titanium front dropouts go to Colorado. Rear dropouts, like the nifty adjustable Syntace dropout that gives you a small amount of wriggle room if you’ve not quite built your rear triangle straight. The list goes on. You’ll have to get your tubing, filler rod and welding gasses elsewhere, but everything else you might need to build your frame can be found here.

The parts are built by the small team of always-be-learning staff, on a mixture of lathes and CNC machines. Their newest staff member, Martin, was in the US Air Force for 18 years working on logistics, since his colour blindness meant the Air Force wouldn’t let him be an engineer – what he really wanted to do. Mark, however, says that if you’ve got a decent grasp of basic maths skills and desire to learn, he can train you to work there. Some staff specialise in working on lathes, some on CNC machines, while others get their skills up on both. While Martin has only been at PMW for six months, their longest standing employee, Joe, has been there since 2004. Like the tenant, it seems the staff want to stick around. It must be more than the high-quality staff meeting snacks that keeps them here – a quick look at the Paragon Machine Works Instagram account gives the impression of a family as much as a workplace, where people are valued and celebrated. There’s even a factory cat called Prince. It feels rather warmer and fluffier than you might expect from an engineering workshop.

Shaving savings

Metal doesn’t come cheap, and neither does tooling, so everyone is always trying to figure out the most efficient sequence of steps to make a product or series of products. With titanium products, Mark estimates they waste eight parts of material to every one part that gets turned into a finished product. With aluminium it’s about 50/50, and steel is about 60/40 waste to product – much of this due to the varied shapes and dimensions of raw stock, or lack thereof, in this variety of materials. It’s no wonder there are lots of barrels of swarf outside, carefully labelled up as to the type of metal they contain.

The bigger the lump of metal you can buy the cheaper it is, so it’s good to start as big as you can. But every cut wastes material, so rather than chopping a length of metal into bottom bracket shell lengths and then turning each individually, with a teeny tiny bit of wastage off the ends of both, shells are made as a pair of conjoined twins, then separated at the last moment. The amount of material cut away to make a pinion gearbox shell would make you weep. And then you’d discover how little the scrap that’s cut away is worth, and you’d weep some more. With aluminium, they can get as much as 10% of the value back for scrap, but for titanium and steel that drops right down to just 1%. So, that pinion gearbox shell in nice lightweight titanium adds up to quite an expensive item to manufacture.

PMW aims to make products in three-month rolling batches, reducing the set-up time and hoping to anticipate the likely number of items required before the schedule rolls around to time to make the next batch. PMW tries to organise batches so that something that needs a really sharp new tool for a precision or detailed cut gets done first. Then the slightly blunter tool may be used to make something else that needs a little less sharpness to get the right finish, and so on. Joe, a machinist and handy mountain bike racer in the early days of mountain biking, has a loupe and a system going on. He knows which tools are heading towards blunt, which are sharp, and which will work on which metal or product. To us, it looks like a pile of miscellaneous drill bits. We resolve not to touch or knock anything over.

Because you’re worth it

This push for efficiency is not so much about creating huge profit margins, as about keeping the products affordable. Paragon Machine Works is unusual in that you don’t need to be a professional builder, order in bulk, or have a business account in order to buy their products. Any shed builder can click away on the website and buy whatever they need. Coco is carefully packing and labelling orders while we’re there, and says she can send out anything from a box of 100 head tubes, to a single cable stop. As long as you pay the postage, there’s no minimum order.

This approach means that Paragon Machine Works gets a lot of orders from hobbyist builders, as well as those making frames for a living. Sometimes the lines between these are blurred, which Mark thinks can be a problem for the viability of the handmade framebuilding industry. If you’re having a go at your first frame, it’s probably going to take you a while and it’s probably not going to be perfect. But you don’t mind, because you’re just having a go – it’s a shed hobby. Then your mate asks if you’ll build something for them, and you give it a go, and you charge them little more than the cost of materials – it’s your mate, you built it in your shed, you’re not offering him a lifetime warranty, and you’re not really trying to make a career out of it, are you?

A few more frames down the line at mates’ rates, and you’re starting to get a bit quicker at it, but still, the price you’re charging for your time is less than you’d get washing dishes down your local gastropub. But when the friend of a friend of a friend sees one of your frames, are you going to suddenly tell them that, actually, you’d quite like to earn £12 an hour for making this, which is going to pretty much treble what they heard that other person paid for it? Well, you could – and probably should – but those early frame prices have set a bit of a precedent, and asking seven grand or more for a bike, even if it is titanium, seems a bit steep.

Except, assuming you’re doing a nice job and the bike holds together and rides well, it’s not really that much, is it? There are mass-produced factory bikes available – and being bought – for that price and then some. Bespoke, handmade and unique are all qualities that elsewhere attract a premium. Have you compared the cost of bespoke curtains to off-the-peg ones? How about a made-to-measure kitchen instead of a flat-packed version? How much more would you expect to pay for the original artwork compared to the print?

If you’re shopping at the enthusiast end of the market rather than the entry level, perhaps you should set more store by the frame you’re hanging your high-end parts on. Which is the nicer bike: the hand-built frame with Shimano SLX groupset and Hope cranks, or the factory carbon frame with AXS everything and a set of XX1 DUB SLs? Or to think about things another way: where is your money most supporting individuals, or bike culture? It’s likely neither here nor there to the big companies whether you buy their bike or not, but buy a handmade frame and you’re supplying an individual with a substantial proportion of their income for that month. In turn, that frame builder is buying a small number of parts from the likes of Paragon Machine Works to enable them to build the bike, and that helps keep a family-sized enterprise going. In a world where we’ve been persuaded to buy real bread, craft ale, locally grown food and artisan products of many kinds, it feels like the framebuilding world has missed the localism trick when it comes to marketing.

Ride bikes, buy bikes

If you’re under any doubt that things are tough for those trying to make a living from framebuilding, you need only look to the stats offered up by Petor Georgallou, the new owner of the UK-based handmade bicycle show Bespoked, and formerly the builder behind Dear Susan Bicycles. He says that of the builders that exhibited at the 2019 Bespoked show, 25% have now ceased trading. That’s a rate of attrition way above the expected rates of small businesses or start-ups – and many of those at the 2019 show had been building for some time, they weren’t new to the game. And there aren’t new builders waiting in the wings to take their place. That all sounds like bad news if you’re someone like Paragon Machine Works.

For now, Mark isn’t gloomy. While new professional builders might not be forthcoming, there are plenty of hobbyists out there, with that sector growing during Covid. Around 75–80% of their business is items sold through their web shop, and about 20–25% is contract work for other companies – not all of it bike based. If you know how to machine, you can make pretty much anything. Sometimes their bike clients grow enough that they can bring their machining requirements in-house – this happened with Moots. While it’s a shame to lose the business, Mark seems pleased to see bike companies being successful.

As he sees it, people riding bikes buy bikes. Some of those people will become enthusiasts, and those people are the ones who are most likely to put their hands in their pockets for the unique experience of a hand-built frame. Supporting bike culture, at whatever level, supports his business. It’s taking the long view, and he puts it into practice locally by supporting a range of non-profit organisations that campaign for and provide local bicycle infrastructure, both on and off road.

Before we visited, we’d heard that Mark and the folks at Paragon Machine Works were thoroughly nice people, and indeed that does seem to be the case. They even rescued us from a cold wet night of camping by putting us up in the on-site apartment. Between the garden, the care for staff, and the support for bicycle culture (and out-in-the-cold journos), it all feels more like a family than a commercial venture. But it is a business, and they’re focused on making products well, and staying as a supplier to the hobbyist as well as the professional, whatever the scale of their operation.

Perhaps you might be one of those hobbyists who’s ready to have a go at building a frame? Or, maybe next time you’re eyeing up a new bike, you’ll have think differently about the concept of value, and have a chat with a framebuilder? Just make sure they charge you for their time.

If you fancy gazing longingly at handmade bikes, giving them a stroke, and talking to builders about their work, then head along to Bespoked, 14–16th October 2022, Lee Valley Velo Park. See bespoked.cc for tickets and further details.

Story tags